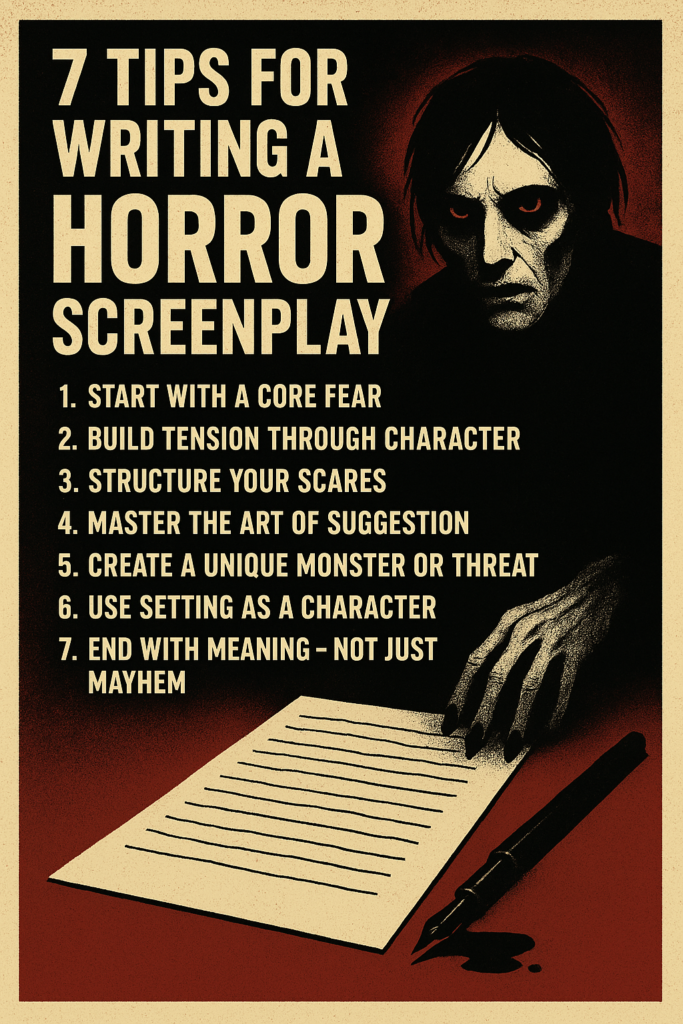

7 Tips for Writing a Horror Screenplay That Truly Terrifies

How to Write a Horror Script That Gets Under the Skin

Writing a horror screenplay is not just telling a story — it’s conjuring fear, tension, dread, and release. But crafting an effective horror script is more than just slamming doors, jump scares, and blood-soaked climaxes.

The best horror films reveal something deeper — about the characters, about society, or about ourselves.

Let’s discuss writing horror that sticks.

Here are 7 essential tips for writing a horror screenplay:

1) Start with a Core Fear — and Make It Universal

The heart of every effective horror film is fear. Not just jump scares or gore, but existential fear — shit that keeps people up at night. First, identify a core fear that your story will explore. This becomes the psychological anchor of your film.

Ask yourself:

- Are you afraid of being watched (like Paranormal Activity)?

- Of losing control (The Exorcist)?

- Of grief and trauma (Hereditary)?

- Of being the outsider (Carrie)?

Then take that fear and make it universal. Good horror translates personal paranoia into shared dread. Jaws doesn’t terrify because of the shark — it’s the helplessness of being out in the open sea with nowhere to run.

Exercise: Write down your own top 3 personal fears. Build a story that sinks the knife into one of these–and twists it.

2) Build Tension Through Character, Not Just Plot

Shitty horror scripts present thin characters simply scream and die. But horror works best when the audience cares. Without emotional investment, the scares are forgettable.

So instead of writing “a group of teens go to a cabin in the woods,” ask:

- Who are they?

- What do they want?

- What are they afraid of emotionally, beyond the external threat?

Character-based tension creates an internal horror that amplifies the external danger. Think of The Babadook — it’s not just about a creepy pop-up book; it’s about a mother struggling with grief, sleep deprivation, and resentment. The monster works because it reflects her inner demons.

Exercise: Before writing your first act, write a one-page biography for your protagonist. What’s their greatest regret? What are they hiding?

3) Structure Your Scares — Don’t Scatter Them

Horror needs structure. Just like a joke requires timing, a scare requires setup and payoff. Your screenplay should build tension strategically, escalating the stakes and layering the fear.

Use the classic three-act structure, but allow the dread to rise like a slow boil:

- Act I: Establish the ordinary world, foreshadow danger.

- Act II: The horror reveals itself; characters try (and fail) to solve it.

- Act III: The horror peaks; the final confrontation occurs.

Within that, consider using the rule of three for scares:

- Tease — something feels off.

- Build — the threat edges closer.

- Strike — deliver the scare (or subvert it cleverly).

Take It Follows as an example: it’s not sudden shocks, but a slowly building sense of inevitable doom. The horror is methodical — and deeply unsettling.

4) Master the Art of Suggestion

Sometimes what you don’t show is more terrifying than what you do.

Effective horror screenwriting often hinges on what’s implied rather than explained. Audiences fear the unknown — so leave room for their imagination to do the heavy lifting. That’s why The Blair Witch Project and The Haunting (1963) are so powerful: they rely on atmosphere, sound, and suggestion.

As a writer, this means:

- Use sound cues instead of visuals in your description (e.g., “a dragging noise from the basement”). Sound is particularly terrifying on a lizard-brain level–never discount the power of good sound design.

- Hold back from over-explaining your monster or killer.

- Let your characters discover clues gradually, making the audience piece it together.

Restraint builds psychological horror — and that lingers longer than any jump scare.

Exercise: In your action lines, describe only what the camera would see or hear. That leaves space for tension.

5) Create a Unique Monster or Threat

Your antagonist doesn’t need to be a literal monster — but whatever represents the horror should be specific, memorable, and symbolic.

Think of:

- Freddie Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street (guilt masquerading as fear of sleep)

- Samara from The Ring (innocence lost masquerading as a fear of technology)

- The Entity in It Follows (fear of intimacy and its consequences)

These threats are effective insofar as they are specific. They follow rules. They reflect internal anxieties. They’re instantly recognizable.

Exercise: ask…

- What does this creature/killer/force represent?

- What are its rules?

- How does it evolve through the story?

The clearer your horror logic, the more frightening (and satisfying) your script will be.

6) Use Setting as a Character

In horror, the setting is more than just a backdrop — it’s often an active force in the story. Think of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, the apartment in Rosemary’s Baby, or the Nostromo in Alien.

Your setting should:

- Reflect the emotional state of your characters.

- Be isolating (physically, socially, or psychologically).

- Have a sense of history or unease built into it.

A good horror setting creates a sense of entrapment. This doesn’t mean your characters can’t leave — it means they won’t or don’t know how.

Exercise: Describe your horror setting using all five senses. What would it smell like? What sound is always just on the edge of hearing?

7) End with Meaning — Not Just Mayhem

A common pitfall in horror screenplays is ending with carnage but no emotional resolution. Gore might satisfy the surface-level thrill, but emotional closure gives the story weight and makes it memorable.

Exercise: Ask yourself…

- Has the protagonist changed?

- What was the horror really about — and how has it been resolved (or not)?

- Is there a final revelation or twist that recontextualizes the story?

The end of The Sixth Sense reframes the entire narrative. The end of Get Out empowers the protagonist and critiques societal norms. The best horror finales work because they tie the emotional arc to the physical horror.

This doesn’t mean every ending needs to be happy — but it should be earned.

Checklist for your ending:

- Emotional closure for protagonist?

- Symbolic or thematic resonance?

- Space for a haunting image or line of dialogue?

Horror Is an Emotional Genre

At its best, horror doesn’t just scare us — it moves us. It’s about grief, guilt, loneliness, identity, trauma, morality, and survival. The more emotionally grounded your screenplay, the more effective your horror will be.

So whether you’re writing a possession thriller, a haunted house drama, or a supernatural slasher, remember: the most important scream is the silent one inside your character’s heart.

Read and Watch Widely

If you’re serious about writing horror screenplays, immerse yourself in both classic and contemporary horror. Read the screenplays, not just the films. Study:

- The Witch (period horror, creeping dread)

- Get Out (social horror and satire)

- A Quiet Place (minimalist dialogue, high-concept scares)

- Halloween (birth of an iconic villain, masterful pacing)

- The Descent (claustrophobia, empowered female protaogonists)

You’ll start to notice how these scripts handle pacing, scene construction, character, and fear. And soon, you’ll begin crafting your own nightmare — one page at a time.

Summary: The 7 Tips for Writing a Horror Screenplay

- Start with a core, universal fear

- Build tension through character, not just plot

- Structure your scares for maximum impact

- Master suggestion — show less to scare more

- Create a unique, symbolic horror element

- Use your setting as an active character

- End with emotional and thematic resonance

Use these tips to craft a horror screenplay that chills readers and grips viewers. Perhaps your story will be the next one audiences whisper about on the walk home, checking over their shoulders for something that may–or may not–lurk behind.

Now go write it. The darkness is waiting.