Three-Act vs. Five-Act Structure: How Story Shapes Screenwriting

Whether you’re writing a superhero epic or a dialogue-heavy indie drama, the underlying architecture of your script matters just as much as your characters and themes. Without a coherent structure, your story lacks rhythm, progression, and emotional payoff.

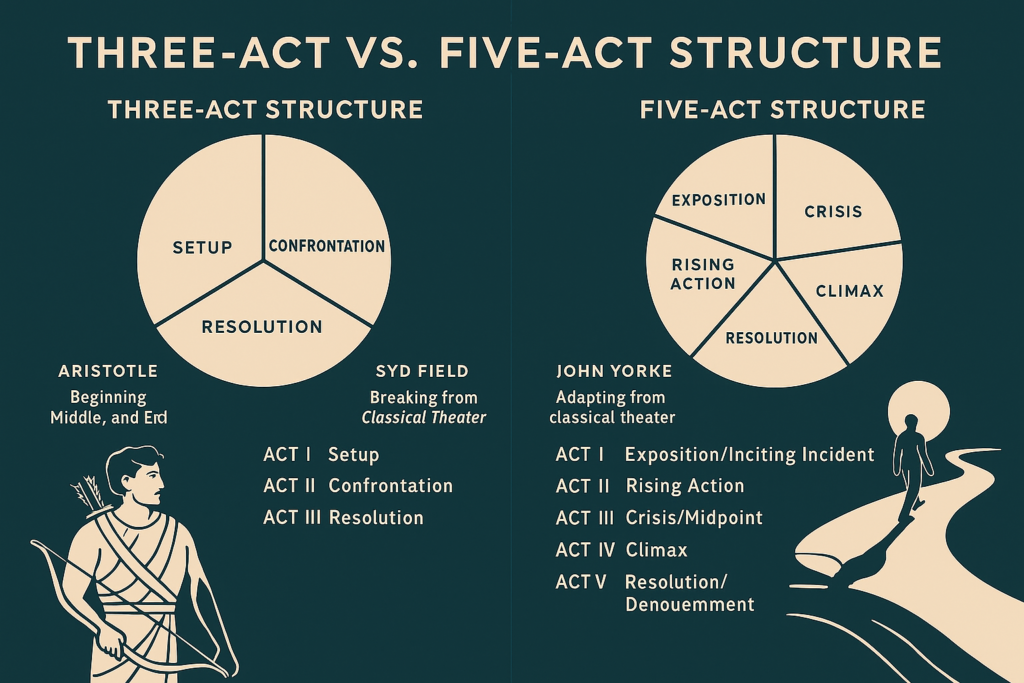

In screenwriting, the two primary narrative frameworks are the three-act structure and the five-act structure. Each model has its own champions—Syd Field and Blake Snyder on one side, John Yorke and some clown called Shakespeare on the other. Each provides a different way to think about pacing, escalation, and turning points.

Let’s explore what each structure entails, how they compare, what their major advocates argue, and how they function in real-world examples.

I. The Three-Act Structure: The Classic Paradigm

The three-act structure has its roots in Aristotle’s Poetics, where the philosopher outlined a simple but powerful idea: a dramatic narrative has–little surprise here–beginning, a middle, and… wait for it… an end.

Aristotle’s Foundations

Aristotle emphasized unity of action and argued that a well-constructed story contains:

- A protasis (setup)

- An epitasis (confrontation or complication)

- A catastrophe (resolution)

While he didn’t specifically refer to these parts of the story as acts, Aristotle’s analysis laid the groundwork for modern structural theory.

Syd Field and the Modern Three-Act Structure

Syd Field’s seminal book Screenplay (1979) turned this ancient concept into a Hollywood standard. Field formalized the three-act structure as:

- Act I: Setup (approx. 25% of the film)

- Act II: Confrontation (approx. 50%)

- Act III: Resolution (approx. 25%)

Field also introduced plot points as key transitions:

- Plot Point I (at the end of Act I): introduces the main conflict

- Plot Point II (near the end of Act II): creates a turning point leading to the climax

Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet

In Save the Cat!, Blake Snyder took Field’s structure and broke it down into 15 beats—moments like “The Catalyst,” “Fun and Games,” “All Is Lost,” and “Final Image.” These beats fall within the three-act framework but offer more granular guidance.

Snyder’s beat sheet is referenced extensively in the screenwriting community because it is simple and helps break down many types of film. Given that it is a formula it risks being, well, formulaic: the BS2 Beat Sheet works best as a way to analyze/edit a written screenplay, not as a template to write a new film.

However, Snyder’s beats are simple and easy to remember. They provide a good language to discuss high, low, and reversal points when analyzing individual films.

Example: The Matrix (1999)

- Act I (Setup): Thomas Anderson (Neo) is a hacker searching for “the Matrix.” He meets Morpheus.

- Plot Point I: He takes the red pill and “wakes up” a fascist. (Oh, sorry, was that out loud?) I mean he wakes up to see reality as it is, and it is a goddamn dumpster fire.

- Act II (Confrontation): Neo trains, learns the rules of the Matrix, and doubts his role as “The One.”

- Plot Point II: Morpheus is captured; Neo chooses to rescue him.

- Act III (Resolution): Neo saves Morpheus and embraces his powers, achieving enlightenment.

II. The Five-Act Structure: Theatrical Precision and Modern Complexity

The five-act structure originates from classical and Elizabethan drama. Most Shakespeare plays are five-act structures. More recently, John Yorke’s Into the Woods revives the five-act model for screenwriting, arguing that it mirrors how humans naturally process narrative.

Structure of the Five Acts (John Yorke’s Framework)

- Act I: Exposition/Inciting Incident

- Act II: Rising Action

- Act III: Crisis or Midpoint

- Act IV: Climax

- Act V: Resolution/Denouement

According to Yorke, the five-act structure offers a more nuanced way to handle escalation, emotional shifts, and character transformation than does the three-act.

Yorke stresses that all stories are about change, and the five-act structure allows for a more granular reflection of transformation.

Why Use Five Acts?

- It allows for mirror points at the center (Act III, the midpoint).

- It separates setup, development, crisis, climax, and aftermath more clearly.

- It aligns well with serialized storytelling (TV, epics, dramas).

Example: Breaking Bad (Pilot Episode)

- Act I: Walt, a chemistry teacher, is diagnosed with terminal cancer.

- Act II: He teams up with a former student, Jesse, to cook methamphetamine.

- Act III: The first cook is successful; Walt begins to change.

- Act IV: Drug dealers confront them; tension rises.

- Act V: Walt kills Krazy-8. No going back!

Note how this all happens within a single 60-minute pilot. Nevertheless, the five-beat rhythm is evident—and such nuanced writing contributes to the show’s serialized, layered complexity.

III. Key Differences Between Three-Act and Five-Act Structure

| Aspect | Three-Act Structure | Five-Act Structure |

| Origin | Aristotle, refined by Syd Field, Blake Snyder | Classical theater, revived by John Yorke |

| Common Usage | Feature films, Hollywood blockbusters | TV dramas, complex features, plays |

| Turning Points | 2 main ones (end of Act I & Act II) | Multiple: inciting incident, midpoint, crisis, climax |

| Midpoint | Often unmarked or secondary | Central to the structure (pivot point) |

| Climax | Late in Act III | Starts in Act IV, followed by reflection in Act V |

| Use Case | Efficient, high-concept storytelling | Layered, character-driven stories |