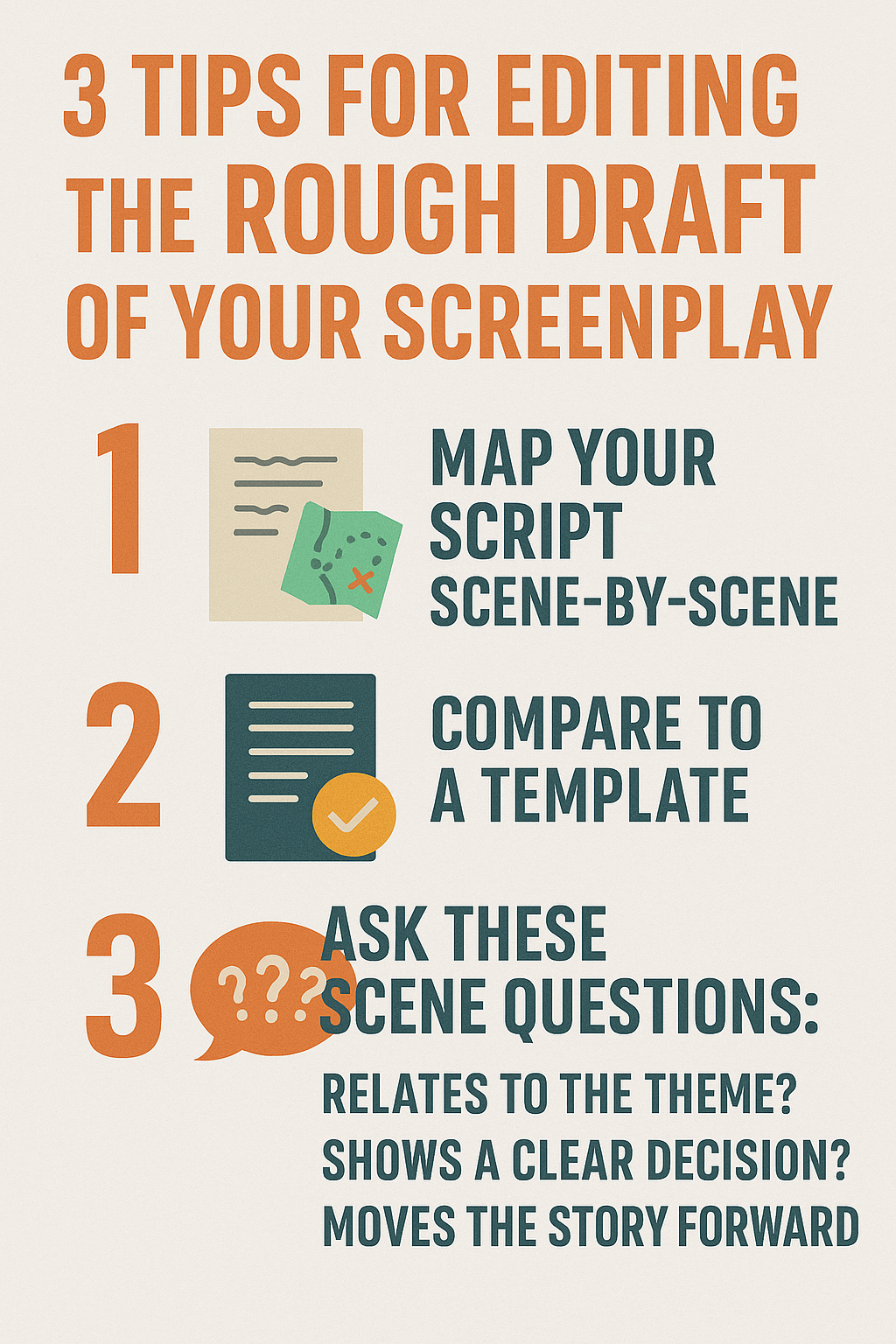

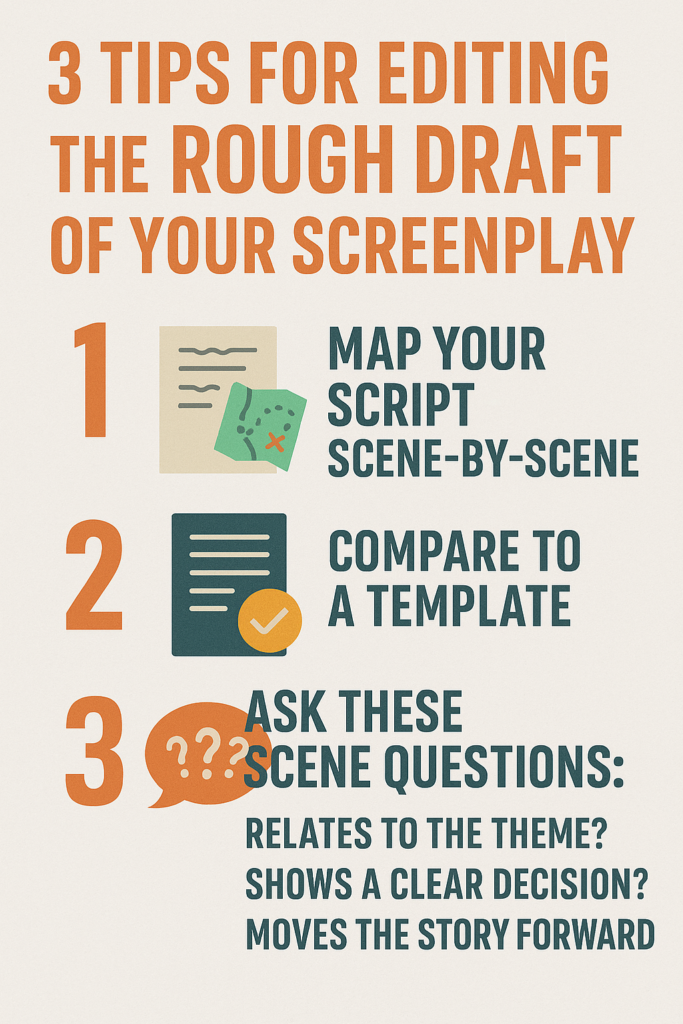

3 Tips for Editing the Rough Draft of Your Screenplay

So you finally did vomited it out. You hit the final page of the very first draft of the script.

And now the creeping dread–this script totally sucks. You’re not alone: everyone’s first draft sucks.*

It’s not ready. It’s messy. No amount of trimming dialogue or fixing typos is going to help it. A few scenes are gold but others are just talky garbage. Dead weight.

Welcome to the rewrite.

One of the first things to realize about screenplays is how finely crafted they are. Writing the script in the first place is maybe 30% of the actual work. The real heavy lifting comes from shaping this raw material into something that is tight, compelling, and ultimately filmable.

However, particularly for first-time screenwriters, the editing process is daunting.

Let’s explore three powerful, actionable strategies to transform your rough draft into a lean, emotionally resonant script. This isn’t going to be lame shit you hear everywhere, at once too vague to lean into and too impractical to fix a script like yours, such as “tighten the dialogue” or “raise the stakes.”

Here, we’ll discuss how to map your screenplay, apply structural templates intelligently, and interrogate the purpose and meaning of each scene for maximum effect.

*Or perhaps you’ve written a perfect script that people just don’t understand, so that’s why they tell you it’s a load of gobshite. I mean it must be a personal flaw on their part. Go somewhere else and live your best life. I’m talking to writers.

Tip 1: Map Your Script Scene-by-Scene

Before you start rewriting, you actually need to know what you’ve actually written.

I mean you did literally (not figuratively) just write it, so surely you have some idea. Except, yeah, nah, mate. You’d be surprised. Hear me out. It’s well worth understanding what you put where, because the structure of the script is often less clear in practice than it seemed as you were writing it.

The easiest way to see what’s actually on the page is to create a scene-by-scene breakdown—essentially a reverse outline of your script.

This is the writers’ version of stepping back from a canvas to look at the painting as a whole. It’s not time to fix your shit at this point. You’re simply mapping the terrain. Making changes might be tempting, but I urge you to hold off.

How to Build a Scene Map

Create some sort of way to log your scenes: a Word document or physical notecard (I prefer these and go through a lot of notecards). List the following for each scene:

- Scene Number

- Location

- Main Characters

- 1-3 sentence summary

- Conflict or Decision

- How it advances story or character

This process gives you a nice, clear overview of your screenplay’s structure.

Watch Out for These Problems

1) Dead Weight

If a scene doesn’t advance the plot, reveal character, or deepen the theme, this scene probably doesn’t belong. Don’t relentlessly hold on to it simply because there’s a clever line or a good joke.

Keep those little glimmers for later–and never permanently delete anything–you never know when it will be useful.

2) Redundancy

Make sure you’re saying something new and fresh in each scene. Too often, you’ll find that you’re saying the same thing twice in two different scenes.

What you’ll learn as you progress is that something that took three scenes to establish in a rough draft can be knocked out in just one scene during revision.

3) Out-of-Place Moments

Sometimes great scenes are just in the wrong place.

Your emotional climax might be happening too early.

A critical reveal might be buried late.

Rearranging scenes can radically improve flow. Notecards, kids. Notecards.

4) Pacing Gaps

If Act Two feels like a morass of expositional dialogue, weird back-and-forths, and general pointless silliness, this is normal. It’s a key place for scripts to stall. Particularly the first half of the second act. This is meant to show us “the Promise of the Premise” as Blake Snyder would have it, but it is a minefield as well because enjoying the premise invites indulgent bullshit.

Mapping helps you see where momentum dips and where to inject new energy.

Case Study:

Take a romantic comedy where the characters meet on page 5. Yet they don’t have an actual conflict until page 45.

This means there’s a long stretch of passive, if pleasant, scenes. This is a major red flag.

To fix this:

- Introduce conflict earlier (perhaps a new, more minor struggle)

- Cut scenes where “nothing changes”

- Move an argument from later to sooner

Rewriting is about making decided choices. Scene mapping helps you make these choices with clarity.

Tip 2: Compare Your Story to a Template (But Don’t Worship It)

Once you’ve mapped your screenplay, the next step is to analyze your story’s shape. This is where templates like Save the Cat, The Writer’s (Hero’s) Journey, or the Yorke version of the Five-Act Structure come in handy.

These are not meant to be followed precisely–please don’t–but they provide an excellent diagnostic tool to see what’s working and what’s not working.

Use a Template as a Measuring Stick

Let’s say you’re using Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat beat sheet (the BS2), which includes key beats such as (but not limited to):

- Opening Image

- Catalyst

- Debate

- Break into Act 2

- Midpoint

- Dark Night of the Soul

- Finale

See where each of these falls on your scene list. See whether these scenes appear early or late relative to the other scenes (there should be roughly similar spacing between the beats). Are any of these missing?

Ask Diagnostic Questions:

- Do I have a clear midpoint that shifts the story? (There are few things in a screenplay that are truly essential. This is one of them.)

- Is there an actual inciting incident? (Why does the protagonist get involved? If this isn’t made clear–and likely out of some sort of duress–then revise.)

- Is there a strong turn from Act 1 to Act 2? (This needs to be a world-changing, irreversible event: Aunt Beru and Uncle Owen just got barbecued; farm boy got nowhere better to go than back to the crazy old fucker and the dodgy space pirates.)

- Does the ending deliver an emotional payoff? (I mean this would hopefully be obvious, again, but there really needs to be a bang of some sort at the end. Is yours sufficient?)

If the answer to any of this is “no,” figure out what scenes you can add, cut, or move to strengthen.

DO NOT Get Trapped by the Template

Templates are tools, not rules.

They offer guidance, not formulas.

Your story may break the mold—and that’s okay (please do!), as long as the audience feels tension, movement, and payoff.

Example:

In Moonlight, the traditional midpoint doesn’t exist as a single moment, but each chapter subtly builds its own climax. A Blake Snyder fundamentalist* would whine that it doesn’t follow Save the Cat—but it still delivers satisfying tension and emotional development.

The goal here isn’t to match the template precisely–it’s to make sure you’re creating intentional structure rather than wandering.

*BS himself, dog rest his soul, seemed fairly open-minded so not a reflection on the man. Acolytes are the fucking worst.

Mix and Match Templates

Try overlaying different models to see which resonates best with your story and tighten accordingly:

- Use The Hero’s Journey for transformation arcs

- Use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle to create simple, iterative structures

- Use John Truby’s 22 Steps to analyze theme and desire

Pick and choose and find the one that helps you ask the best questions of your materia

Tip 3: Ask the Three Scene Questions

Once you’ve zoomed out with your map and your structure, it’s time to zoom back in.

The final (and perhaps most powerful) editing tip is to interrogate each individual scene.

Ask yourself:

i) How Does This Scene Relate to the Theme?

Theme is what your script is about, beneath the surface.

- If your theme is about control vs. freedom, does this scene illustrate someone asserting (or losing) control?

- If your story is about isolation, how does the scene deepen (or resolve) the isolation?

Every scene doesn’t need to explicitly acknowledge the theme, but it must resonate somehow with the theme (like playing a totally discordant chord). If the scene is telling a different story from the theme, then it will seem out of place.

Remember, each theme must feel as if it is a meaningful part of the film’s emotional makeup.

ii) Does Someone Make a Clear Decision?

Stories are driven by choice under pressure. If the characters–particularly the protagonist–never choose anything, the story remains at idle.

Look at each scene:

- What is the inherent dilemma/conflict?

- What decision is made?

- Does this result in some sort of desire, resistance, or shift in perspective?

If the answer to any of these things is no, you might well be looking at a passive scene that needs to be cut or rewritten.

Bonus tip: Great decisions–in writing, that is–are flawed but understandable.

What makes Don Draper such a well-painted character is that 90% of what he does is sort of terrible, but you know him well enough to understand why he does it.

iii) Does the Scene Move the Story Forward in Plot or Character?

This is the litmus test. A scene must do at least one of the following two things:

- Advance the plot (something changes in the external world)

- Deepen the character (we learn something new or see transformation)

If it does not do either of these things, then it is probably dead weight.

This is even true for quiet, introspective moments. Even someone staring out a window must indicate a noticeable shift:

- Does the character make a choice?

- Does the character’s emotional state change?

- Does the audience understand something new?

If the answer to any of these is “no,” then this scene needs to be cut or rewritten.

Scene Audit Example

Let’s audit a hypothetical scene from a crime drama:

Scene: Detective X interviews a witness in a diner. The witness gives some vague answers, but nothing useful. Detective X thanks him and leaves. End scene.

Weak Version:

- No new clues revealed

- The Detective makes no decision

- This teaches us nothing about the Detective or the case

- The theme (lets say “justice vs. revenge”) lies flat

Solution: In a rewrite, the Detective can pressure the witness, risking her reputation or a relationship.

Perhaps the Detective gets too aggressive and it backfires. Now that we see her flaw, we move the plot, and we hit the theme.

(Think Popeye Doyle beating up suspects or picking up nubile young ladies on bicycles or living in a bedsit. You learn something about who this dude is, and little of it is complimentary.)

How All Three Tips Work Together

Let’s say you’re editing a messy first draft of a sci-fi thriller. Here’s how these three strategies work as a process:

- Scene Map: The entire first act has five scenes that don’t introduce conflict. You cut two, move one forward, and rewrite the inciting incident into scene 2.

- Template Test: Use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle and realize you’re missing a “Return with the Elixir” moment. At this point, add a new scene showing the protagonist using what she learned and experiencing a personal sacrifice.

- Scene Interrogation: In scene 44, a different character watches a news report–even though this contains useful information, the character doesn’t react. In a rewrite, the character throws the remote at the television, makes a phone call, and agrees to something he might just not be able to back out of.

Notice how, even with minor tweaks such as these, the story now seems tighter, stronger, and more alive.

Rewriting Births Creativity

Editing isn’t just about fixing typos or deleting filler dialogue. It’s where the real craft of screenwriting emerges. Editing means shaping story. It means structuring emotion. It means sculpting meaning.

- Mapping scenes gives you clarity.

- Using templates gives you structure.

- Interrogating scenes gives you purpose.

Think about writing a first draft as mixing water with clay. Editing, on the other hand, is sculpting. Don’t rush the editing process. Have an idea of how you will attack it.

Whenever you feel lost, go back to the scene map. Look at the big picture. Think about the little things you can do today to make it better.

When you’re done with this pass, map it again and start over. You’ll get there.