Conclusions vs. Sustainable Narratives: Are Screenwriters Ready to Live Without Endings?

Conclusions are for young people. They’re bedtime stories so you can get to sleep. Adults need sustainable narratives: ongoing stories that don’t end. – Douglas Rushkoff

Advice on how to write a good drama stretches back (at least) to Aristotle.

Interestingly, however, is how tightly we cling to some of Aristotle’s main assumptions 2500 years later. From the Poetics to Save the Cat, three-act, five-act, whatever, we’ve been wading through variations of the same structure: setup → complication → climax → resolution.

It’s basically a sex act from the male perspective.

Obviously we’re familiar with this rhythm. In fact, the structure is so deeply embedded that 1) we simply ignore its existence or 2) we confuse it for an innate feature of our brain’s wiring. Authors like Joseph Campbell would argue that such a story structure is, in fact, a born-in feature of the human psyche.

Of course there’s no actual way to prove that, and it’s equally possible that Campbell’s enduring legacy is just a product of coming up with this one idea and going hog wild: when you have an figurative (not literal) hammer, everything starts to look like a nail.

(Just ask “theory” people in the humanities about that one.)

This is demonstrably not the only structure in town; all you need to do is look at European cinema to see the occasional very stark contrast. Michael Haneke, Gaspar Noë, and countless others would beg to differ.

Mercifully, we might–in the Anglo world, at least–finally be breaking free of Aristotelian structure.

That’s not to say we need to get into navel-gazing art films, Andy Warhol eating a Burger King, or Kenneth Anger perving on hot rods. Rather, I’m talking about a slow but steady emergence of sustainable storytelling: stories that don’t end, or don’t end cleanly. Stories that leave you not with a tidy solution, but new and better questions.

Stories that play an infinite game.

Act I: The Tyranny of the Conclusion

Modern society is addicted to conclusions.

Our cultural output has been shaped by centuries of storytelling that privilege conclusion over continuity. The hero must slay the dragon. The lovers must kiss (or say goodbye). In short, the problem must be solved.

(And we get butthurt if it solves in a way that doesn’t seem “right.” But what’s right is subjective. Right?)

Fine. Resolution feels good. It tickles the right receptors in the brain. It helps shape and mold experience when life refuses to do so. Hollywood understands that this sells. Politicians, to our inevitable detriment, understand it even better.

Tidy endings equal satisfied audiences. Repeat customers. Blah blah blah.

But look around lately, and you’ll see a new appetite forming. An itch for something else.

Act II: The Rise of the Sustainable Story

Let’s look at two of 2024’s most celebrated films: Anora and The Brutalist. Neither offers a conventionally satisfying conclusion. In fact, they both actively resist resolution.

- Anora draws us deep into the emotional complexity of a woman caught between agency and exploitation. Just when we think it’s all been laid out, it sidesteps our expectations and ends on a note that perhaps satisfies on a poetic level–but it definitely raises more questions than it answers.

- The Brutalist paints a grand, metaphysical portrait of art, ambition, and architecture. Its final moments–from Harrison’s disappearance onward–literally (not figuratively) raise questions rather than answering them.

These films can be seen as the latest products of a cultural evolution that has been underway for decades. It is most apparent in the best moments of serialized television.

Look at The Sopranos, Mad Men, Twin Peaks, The Leftovers, or Atlanta. What ties these works together is their openness, refusal to give easy answers; in short, their infinite game.

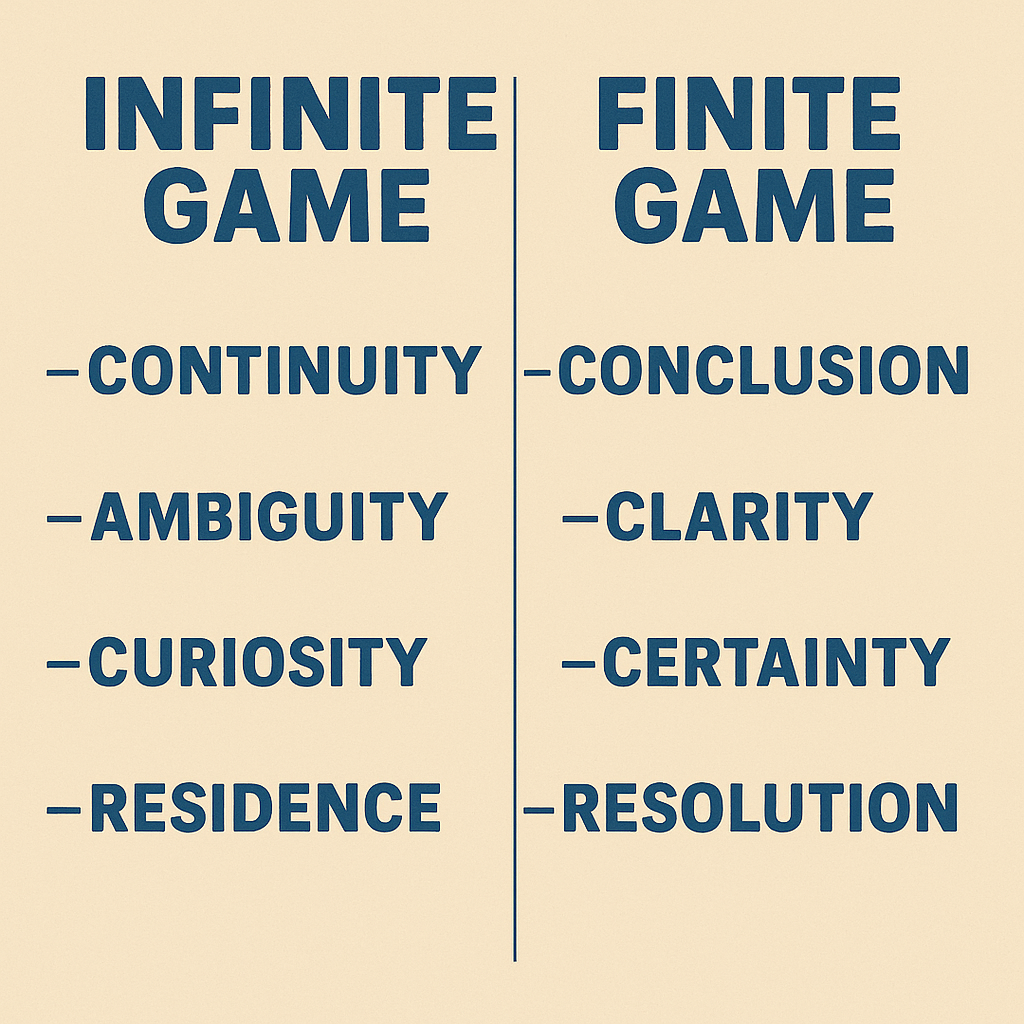

The Infinite Game

In his 1986 book Finite and Infinite Games, philosopher and religious studies professor James P. Carse distinguished between two types of games:

- Finite games are played to win. They have rules, boundaries, and an endpoint.

- Infinite games are played to keep playing. Their goal is not to win, but to sustain the play.

Put another way, admittedly crudely but for the sake of visceral understanding: it’s effectively men in bed vs. women in bed.

Now: traditional stories are finite games. Who wins, who dies, who gets the guy, who enacts revenge.

Sustainable storytellings, however, doesn’t look for victory. It looks for presence. You don’t want the story to end. You want to live in the world a little bit longer. Ideally, when the final frame flickers past, it invites you into metabolize the journey as something ongoing.

Act III: Narrative as Atmosphere

Let’s revisit Mad Men.

Don Draper’s final moment—him meditating on a cliff in Big Sur, with an enigmatic smile, has been interpreted a zillion fucking ways. It’s not clear whether Don has achieved enlightenment, peace within himself, or he’s just pleased with himself for figuring out how to commoditize the peace movement.

But that’s sort of the point. We don’t know. Even better, it’s not as if those three things are mutually exclusive. Honestly, it was probably a bit of each.*

The point is that we don’t know.

The entire span of Mad Men was about Don’s struggle to change. He came so close so many times and fucked it up gloriously. Every. Single. Time. The entire show was about keeping the game going: raising more questions than answers.

Likewise, the famed cut to black in The Sopranos means that the audience must live with the unresolved tension that Tony was forced to live with. Arguments as to whether “Tony lived” or “Tony died” totally miss the point. They’re playing the wrong game.

Storytelling can be about existence, not event or spectacle. Creating the environment for existence is the point of a sustainable narrative.

Case for the Three-Act Structure

Three-act structures are not by any means obsolete. They clearly work, and that is a rare thing these days. Many people lean into processing their existence in this way. These types of narratives can propose at least a nudge in the right direction.

Remember, though, that there’s a good argument that this is nurture, not nature.

Insofar as the Hero’s Journey is merely a function of how we have been trained to experience stories—through myth, religion, Hollywood, and a thousand bedtime stories–then we can be retrained.

The Cliffhanger as an Ethical Gesture

To insist on resolution is to insist on a single truth. This is demonstrably not how the world works. Climate apocalypse, creeping authoritarianism, stultifying rectangles in our pockets, etc. are not finite games (despite the best efforts of those at the top).

These things do not resolve. They evolve.

Remember, people who live through the collapse of a civilisation might experience something–but it is probably not identified as such until centuries later.

Consider even something as apparently definite as Terence McKenna’s proposal that the world would end in 2012. I’m fairly sure it actually did end then–I mean look out the window for fuck’s sake–but no one noticed.

ANYWAY–

What does it mean when we allow a story not to end?

This means to accept ambiguity. To live inside a question, not leap to an answer. To open space for complexity.

This is maturity. Being a fucking adult. Not expecting bedtime stories.

How to Write the Sustainable Narrative

We must then begin by reframing our goals. It’s not about “How does it resolve?” Rather, it’s about:

- “How can I create an environment that people want to experience even after the credits?”

- “How is it possible to ask new and better questions?”

- “How does the character grow without living happily ever after?”

- “How is it possible to create stakes without ultimate closure?”

Here are a few practical guidelines:

1) Focus on Rhythm

Instead of building to a single climax, build in waves.

Twin Peaks introduced—and then obliterated—central mysteries, only to introduce new ones. Granted, some of this became a bit cack-handed after Episode 14, but bear with me.

Think of Twin Peaks as an exercise not in payoff, but in vibe. The rhythm of that world was the story.

In fact, the payoff of learning Laura’s murderer actually threatened to derail the whole project and took a good ten episodes to get back to something approaching the original 14 episodes.

Exercise: Write a short scene where nothing is technically resolved, but the emotional tenor among the characters experiences a dramatic shift. The shift, kids, is what you’re looking for.

2) Let Your Characters Breathe

Allow characters to find a dynamic stasis. Remember episodic television: characters don’t need to resolve; they need to pulse.

Exercise: Choose a character you love and write three scenes from different points in this person’s life. Show change, but avoid epiphany. Embrace contradiction.

(You’ll notice that this is, essentially, the structure of The Brutalist.)

3) Design for Return

A sustainable narrative invites another visit. Make your world detailed enough that people want to re-enter it. Layer. Don’t feel that everything needs to be explained.

Shows that people watch obsessively, like The Wire, are the type where the complexity makes it rewatchable. It is a story not to watch, but to inhabit.

Exercise: Write a scene with a diegetic element (think the soap opera in Twin Peaks) that hints at a deeper world. Don’t draw attention to this element–just let it be.

4) Rethink the Cliffhanger

The cliffhanger doesn’t always have to be cheap suspense–particularly if you know there’s not a resolution coming on next week’s episode.

When done right, a cliffhanger is a statement of narrative sustainability. It doesn’t give everything, but it gives enough for the viewer to keep thinking. To make up her own mind. To engage with the world even more once outside the cinema.

Exercise: Write the final paragraph of a story where something is about to happen—but we never see what it is. Make the anticipation feel like the ending.

OR

Write a full scene with a conclusion and cut it off at the beat immediately before the climax.

The Future Is Open-Ended

Hopefully, all this means that we are, culturally, entering a new phase of storytelling.

Of course the old model works, and it’ll still crank out its money shots well into the future. Meanwhile, something else–rooted in patience, ambiguity, and endurance–is rising. We understand that stories can have meaning even without capping them off with a conclusion.

In fact, they are more meaningful when they don’t.

This is even more important in the flaming shitheap of the present moment. We must endure, and stories can help us do so. To do so, however, they must emphasize continuity, curiosity, and resonance.

The Writer as Gardener

The old saw is that screenwriters are “architects.” Frankly, if you knew how abused and underpaid architects are, you’d probably want a better analogy.

So to hell with the architect. It’s time to be a gardener.

Plant a story. Prune it. Let certain aspects grow wild. You accept that you can’t control everything—to paraphrase the dearly departed Tom Robbins, sometimes you pull a rabbit out of a hat and the rabbit takes over the whole story–embrace the beauty of what emerges.

After all, life doesn’t always resolve, and that’s okay. Or hopefully it’s OK because we don’t have a choice in the matter.