How to Create an Unlikeable Protagonist

“I just felt like the protagonist wasn’t likeable.”

Shoot me now.

For those of us who have been writing for more than five minutes, it’s pretty fucking obvious that any of the most iconic protagonists in film and television are not likeable at all.

Alcoholics. Drug fiends. Criminals. Narcissists. Killers. And yet we follow them and root for them.

This begs the question: is this advice wrong? Or are we misunderstanding what “likeable” actually means?

The question “does your protagonist need to be likeable?” comes off as a paradox, but I argue that it is actually asking the wrong question.

Let’s explore what a better question might be.

Part I: What People Mean When They Say “Likeable”

If a person says your character needs to be “more likeable,” she’s rarely asking for some tepid goody-two-shoes. This person is likely saying, in a particularly cack-handed way:

- “I don’t understand why they’re doing this.”

- “I’m not invested in what happens to them.”

- “I wouldn’t want to spend time with this person.”

What this reader is gagging for, then, is a character they can connect with. That raises two important questions:

- Is this character relatable in some way?

- Is this character compelling enough to follow?

Let’s tackle those ideas separately and introduce the power of the unlikeable protagonist.

Part II: The Power of Relatability

Relatable does not mean nice. It means human. Even for a protagonist who is selfish, self-destructive, or flat-out immoral, we can understand this person’s emotional engine.

A good example of the unlikeable protagonist (naturlaly because everyone loves him, despite him being sort of a douche) is Don Draper in Mad Men.

Don cheats. He lies. He manipulates. On paper, he’s definitely not the sort of person you’d want to be friends with. However, women wanted to be with him and men wanted to be him. For eight full years.

Ultimately, this is because we have a window into what made Don: an abusive childhood, a desperate identity theft, a nagging feeling that he will ultimately be found out. Particularly given that he’s a battlefield deserter–a capital crime, no less–this is given literal (not figurative) life-or-death weight.

Crucially, we aren’t asked to forgive Don; rather, we are asked to understand him. Don is a total badass at his work. His campaigns are brilliant and emotionally resonant. In pitching his constructions, we understand that there is a (constructed) version of Don that makes total sense. The swirling between professional hotshot and personal hot mess is fascinating and, throughout the series, never abates.

The audience doesn’t need to approve of Don. However, we as the audience can see ourselves in Don’s shame and attempts to construct meaning in his life.

Rather than likeability, go for relatability.

Part III: The Magnetism of Compelling Characters

Of course no one would argue that you can relate to someone like Hannibal Lecter–an urbane, highly educated, psychiatrist who also happens to be a goddamn cannibal–but the man is so compelling that the audience can’t look away.

Hannibal is charming and brilliant. Highly cultured. Zero fucks given. Notably, also, scenes (we’re talking about Silence of the Lambs only here) featuring Hannibal are fraught with tension and danger. He is unpredictable, but always interesting. His contradictions–suave conversation partner vs. violent murderer, etc.–are endlessly fascinating.

So that’s compelling: the character needs not to be good, but interesting. Let the character generate questions in the viewer’s mind:

- “Why is he doing this?”

- “What will she do next?”

- “What happens if he gets caught?”

Mystery. Charisma. Contradiction. Risk. Compelling protagonists keep us watching.

Part IV: The Moral Code Trick

The personal moral code is an excellent way to encourage empathy with an unlikeable protagonist.

Even if your protagonist behaves terribly, they can be guided by a specific code of ethics, one that’s clear and consistent, even if it’s warped (and it usually is).

When that code is challenged—almost always when others behave worse than your protagonist—it allows the audience to see the world through via protagonist’s logic.

Example: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)

Henry kills people. He’s terrifying. But we learn he has a hard rule: no sexual violence. When his partner Otis breaks that rule, Henry kills Otis.

This hardly makes Henry an upstanding citizen. But the contrast makes his rule visible. And that clarity gives us a chilling insight into how he sees the world.

In Henry’s mind, at least, he is the lesser evil—and the story gives us just enough alignment to exist within Henry’s twisted POV.

Example: Seul contre tous (1998)

In Gaspar Noé’s Seul contre tous, “le Boucher” (the Butcher, because he is an actual butcher, naturally) is a misanthropic racist with a persecution complex.

To le Boucher’s mind, everyone is against him. He believes his life has been driven into the ditch by a hostile society.

As le Boucher spirals into madness, the consistency of that worldview remains strong. It provides a warped compass. It’s objectively untrue, but the audience understands how he justifies his descent. This is storytelling: empathy floods the gap between objective horror and subjective reasoning.

The moral code doesn’t need to be moral. It needs to be coherent.

Rather than watching chaos, it is watching a pattern unfold.

Part V: The “Save the Cat” Shortcut

Sometimes, audiences need a single gesture that says: “This person is worth investing in.”

Coined by Blake Snyder, “saving the cat” refers to a moment early in the story where the protagonist does something kind, noble, or brave. It makes the audience say, “Okay, I like this person.” Like–wait for it–saving a cat stranded up a tree.

It’s simplistic to the point of self-parody, but the psychology of it actually more or less makes sense. This is particularly true if the rest of the story gives us reason to doubt the character’s goodness.

This is a fine trick to use if you’re really stuck, but it’s hard to imagine Travis Bickle climbing a tree to shepherd his neighbor’s cat to the ground. Just saying.

If you go down the STC route, remember that this gesture must feel honest to the character. If your misanthropic loner–out of the blue–saves a toddler from drowning, this needs to reflect some sort of deeper contradiction in the character’s life. Otherwise it becomes mere pandering to the audience.

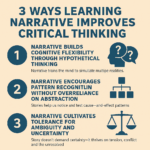

Part VI: Empathy Through Lens

Story provides a lens through which to see the world. And that lens shapes how the audience experiences morality, motivation, and emotion.

Great storytelling distorts the lens so that we can see the world through someone else’s eyes.

You don’t need a likeable protagonist. You need a protagonist who makes sense—on her own terms.

Don Draper (Mad Men)

Why we stay with him:

- Brilliant at his job

- Deeply wounded

- At war with his identity

Despite his flaws, his story is about a man who wants to be better, even when he doesn’t know how. We follow him because his failure becomes ours.

Daniel Plainview (There Will Be Blood)

Why we stay with him:

- Relentless clarity and drive

- Deep contradictions

- Zero fucks given

Plainview is arrogant, violent, and greedy. But he is so committed, so decisive, and so willing to do anything, that we are mesmerized by how far he will go. He never pretends to be anything he isn’t–particularly moral.

Part VII: What To Do In Your Own Writing

If someone has the temerity to give you that stupid note, here’s what the person really means.

(If they actually mean “more goody-two-shoes” you might consider shopping your script elsewhere).

To wit:

- Is the character’s motivation emotionally legible?

- Does she operate by a consistent (if twisted) moral code?

- Do her actions generate curiosity or suspense?

- Does the story’s lens help us understand, if not approve, of her decisions?

- Is there a moment—however small—where we’re allowed to feel something for her?

If the answer is NO to all of these, then get to work making at least one or two of them a YES. Congratulations: your character will become someone the audience can empathize with.

(Now it is entirely possible that these are all in order. In that case, the problem may be something else.

The stakes could be higher or more ironic, character motivations could be clearer, or the balance between the protagonist and they story’s inherent irony might be off.)

Likeability Is a Load of Shite

Now you understand:

Likeability isn’t the goal. Relatability and fascination are.

Audiences don’t need to like your character. They need to understand her (or want to do so). Fear her. Laugh at her. Pity her. In short, the audience must feel something powerful enough to keep their eyes away from TikTok.

In that case, create a protagonist worth watching.