How to Create a Compelling Protagonist —

Two Examples of How to Engineer the Story to Make the Protagonist More Interesting to the Viewer

This isn’t gonna start how you expect it to.

Creating a compelling protagonist is rarely about creating The Most Interesting Person in the World. After all, to have a title such as that, all her deeds must be in the past. What we want is the story of how she got that way.

So… we need to think about how compelling protaognists as rising from the interplay between character and story.

In other words, a compelling protagonist comes not from being inherently interesting, but from being the perfect person for the problem at hand–that is, the story.

A good story isn’t simply something that happens to your character.

A good story is something that must happen to your character if she is to grow.

That is, we want to continue watching (or reading your screenplay) not just because a character has been metaphorically* thrown in a hole and is trying to get out–that much is obvious on the surface–but because we are emotionally invested in this character’s change.

That means that we need to understand what’s at stake for this character’s internal life as well as external life if we are meant to care even a little bit.

Of course this is easier said than done. So how can you make sure that you have the best possible story for your hero–or, in reverse, the best possible hero for your story?

This guide will give you five real-life examples of excellent balances between story and character and break down specifically what makes these stories work well.

Finally, you’ll have a chance to answer a few simple questions that will put you well on your way to creating that elusive, compelling interplay between the story and your character’s weakness.

Let’s dive in.

*Or literally in The Dark Knight Rises…

Hey! You can download the PDF version of this with THREE MORE EXAMPLES (Alien, Fight Club, and Pulp Fiction) here:

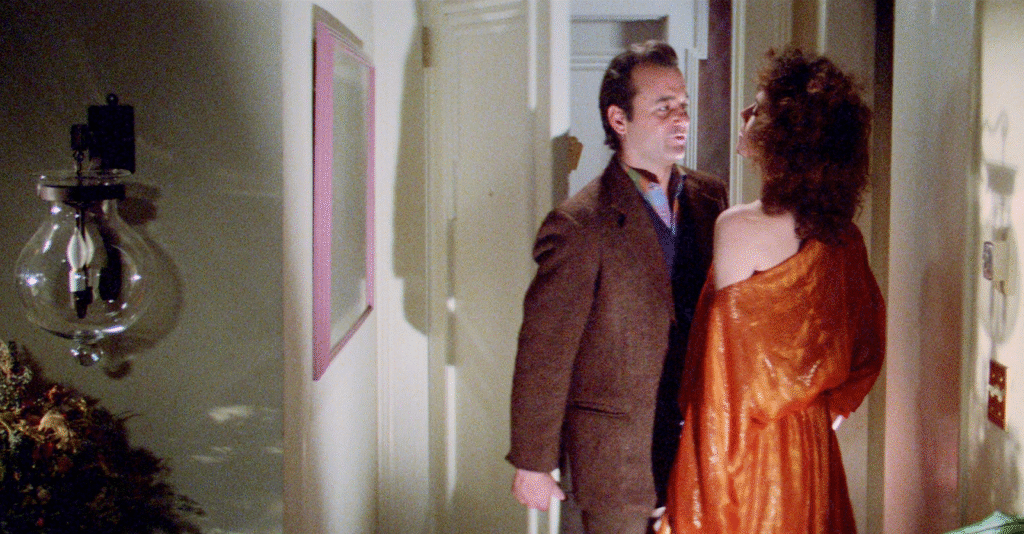

Example: Ghostbusters

It’s always worth asking yourself why a character is the worst person for the task she’s handed.

This is especially apparent in how the External and Internal problems are blended. Let’s look at an example.

In the case of Ghostbusters,* we see from the jump that Venkman is a womanizer and a charlatan. He’s talked his way into two (!) Ivy League PhDs, but he is, as we are told, a “poor scientist.”

Venkman’s weakness, then, is that he’s all talk and no action. He’s a charmer and a dilettante. These qualities may often be overlooked, if not flat-out rewarded, in academia.** Nevertheless, Venkman is surely unable to survive “in the private sector,” as Ray is quick to remind him.

External: Zuul, a resurgent Sumerian deity, threatens to destroy New York City.

External Problem: When dealing with a pissed-off ancient god, it’s not reassuring to have someone liberally painted as an incompetent charlatan be the only person able to protect you.

Internal: Venkman, for once, actually falls for a woman: Dana Barrett.

Internal Problem: Dana is unimpressed and Venkman soon realizes that he’ll have to be a better man to charm her.

Crossover Problem: Unwittingly, Dana has become the Gatekeeper for Zuul’s re-entry.

Notice, then, how resolving the story–if Venkman is successful against Zuul, he will have to act instead of talk–directly implies that he will become a better man during the course of the story.

If everything goes according to plan, this may just make Dana take him seriously (if she doesn’t get barbecued in the process).

*For the sake of argument, let’s take Venkman as the protagonist rather than the collective team.

**Put the shiv back down your trousers–this is spoken as someone who is literally (not figuratively) a university lecturer.

Example: Back to the Future

Sometimes you start with an interesting concept, say, “a 1980s teenager time travels to the 1950s and experiences culture shock.”

A cute idea does not drive a story, however, so it’s useful to go back and query what the worst thing that could possibly happen to our hero is.

It sort of seems obvious in retrospect, but it’s really quite brilliant how Gale and Zemeckis teed up the external conflict: when Marty is sent back to the 1950s, the first thing that happens is that he disrupts his parents’ meet-cute.*

External: Marty needs to get back to 1985.

External Problem: Marty’s appearance prevents his parents from getting together, so this sort of needs to be fixed before he makes it back to the future (ahem).

Internal: Marty comes from a family of losers and deeply fears becoming yet another in a long line of losers, particularly when his musical dreams are dashed by the stodgy principal.

Internal Conflict: To save his own skin, Marty must teach his teenage father, George, how not to be a loser.

Crossover Problem: Unless Marty can face his own insecurities, playing on stage to get his parents to hook up, he’ll simply…

…never finish the sentence because he ceased to exist.

*And by “meet-cute” I mean “meet-creepy.”

Conclusion

Remember, a story that compels the viewer will of course raise the stakes in terms of the external problems facing the protagonist.

However, if you think about how hard it is to remember the final act of most movies (except, say, Carrie), perhaps that’s because what we’re really focusing on is the internal journey of the protagonist.

Still, it’s not enough to do what many modern films do: mention an internal problem or concern at two or three strategic points and call it job done.

For example, in 2023’s Evil Dead Rise, Beth finds out at the beginning of the film that she’s pregnant.

This isn’t really brought up again in any meaningful way, but somehow we’re supposed to intuit that–having watched her sister, niece, and nephew be possessed by an evil demon and then having to slaughter each of them, ultimately cooperating with her other (surviving) niece to feed her undead sister through a wood-chipper–she’s really learned something about her capacity for motherhood.

Right?

Right?

Well, I mean, no. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the pregnancy business is simply bullshit out of some paint-by-numbers screenwriting book.

A truly good setup, as we have seen, plays the internal struggle of the character off of the external situation. Ultimately, the two situations will cross over such that completing the external task will give your hero the chance to overcome her internal struggle.

Exercises to Create Your Compelling Protagonist

Here are a few questions that will help you create a story that is perfect for your hero, or, if you have a great story, you can work in reverse to create the perfect hero for the story.

- Given my hero, what is the worst possible thing that could happen to her? / Given my story situation, who is the least capable person to handle this situation?

>This doesn’t need to be truly “life or death,” yet it is an existential crisis insofar as it will require internal change to overcome.

- What is my hero’s external situation at the beginning?

>This is an actual complication that throws a wrench in the character’s day-to-day. Still, it might just be an interesting situation, until…

- What is my hero’s external problem?

>This is where the rubber hits the road: the complication becomes a true crisis.

- What is my hero’s internal situation at the beginning of the film?

>This should be less-than-ideal, yet not so dire as to require immediate change.

- What is my hero’s internal problem?

>How does the external situation challenge the hero’s very identity?

If you can answer each of these questions, congratulations! You’re doing better than about 95% of produced Hollywood films these days.

If you want some extra practice, look at the iMDB Top 250 films and do the same exercise for 5-10 of these.

Remember, you can download the PDF version of this with THREE MORE EXAMPLES (Alien, Fight Club, and Pulp Fiction) here: