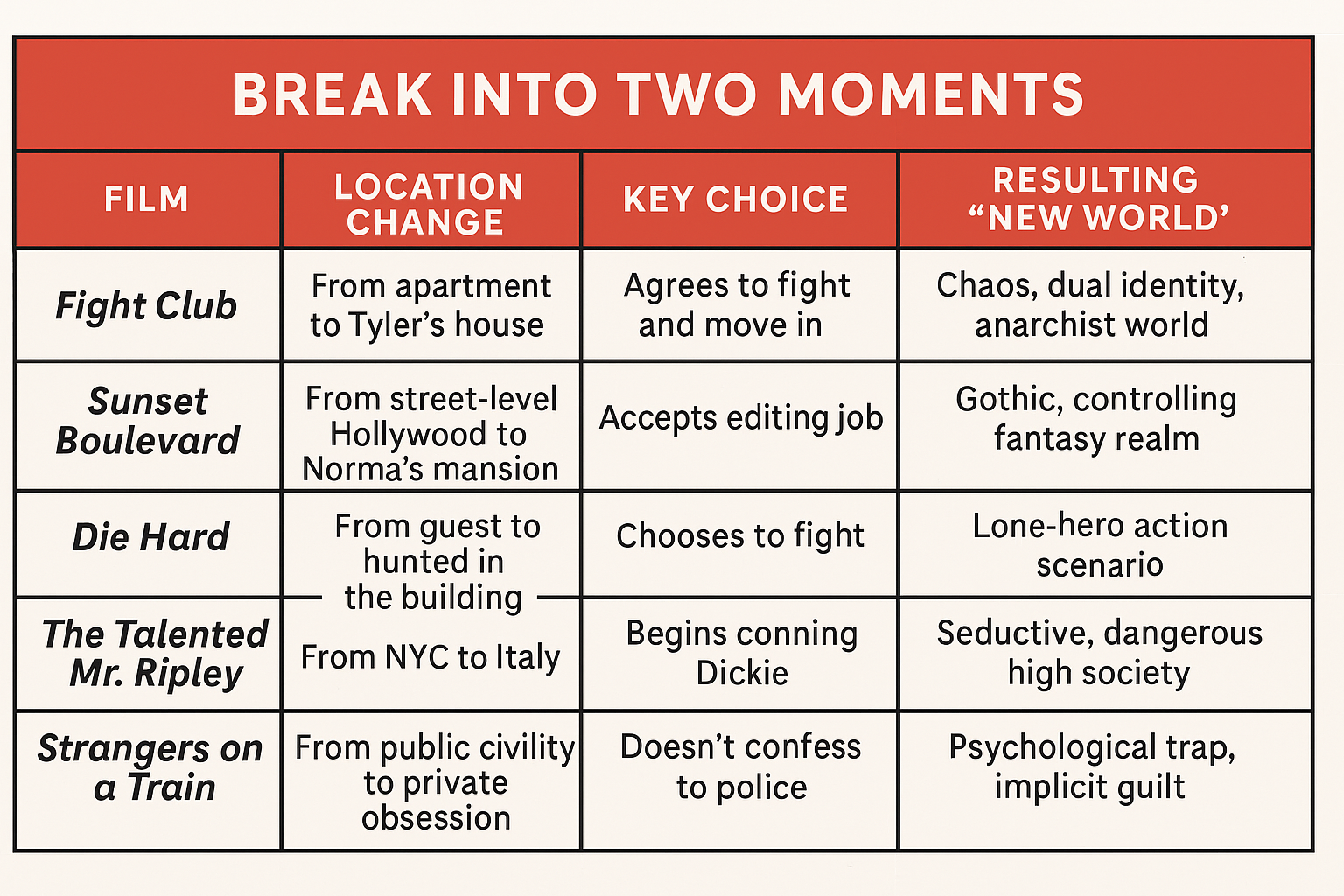

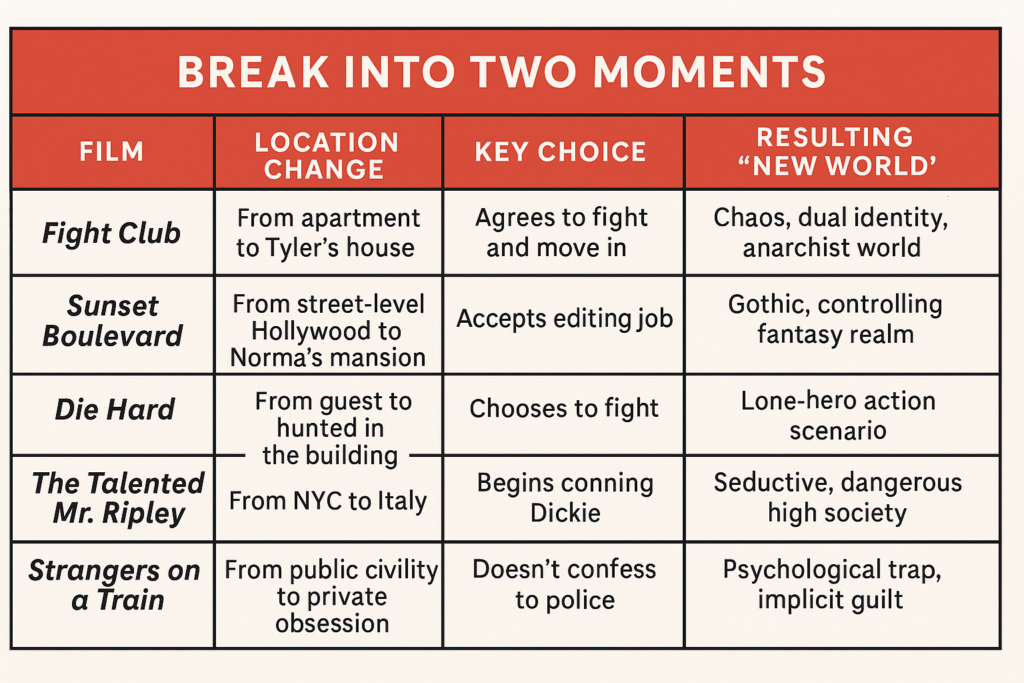

Five Examples of the Break Into Two for Screenwriters

Those of us who geek on screenplay structure have a tendency to refer to the Break Into Two–which I may well call the Act II Break, so forgive me–as some sort of specific moment that shifts us into the new act.

In practice, however, it’s often not that clear. What we see is that the shift into Act II is often a cluster of scenes that 1) create an often irreversible rupture of the character’s everyday reality and ultimately ends in 2) a choice that define the character’s new reality. You’ll notice that most of the time, this is metaphorically represented by a new physical location.

This is obviously intentional: the shift in location gives a physical expression of the character’s psychological shift. It demonstrates that a line has been crossed. This new world will likely demand more of the protagonist than the one she’s previously inhabited.

With all this in mind, here are five examples of clean Break Into Two moments from classic films–plus advice about what you can take from each of these and put to use in your own work.

- Fight Club (1999): From Explosion to Chaos

Scene Cluster:

- Event: The Narrator’s (Jack) apartment blows the fuck up.

- Choice: He chooses NOT to call Marla and instead dials Tyler. They meet at a bar, and Tyler speaks the famous line “I want you to hit me as hard as you can.” Once Jack complies, his old world is firmly dead.

- Location shift: Jack moves into Tyler’s Paper Street house.

Fight Club’s structure is often misinterpreted (more on that elsewhere), but this Break Into Two is clear as day. Jack had previously lived a somnambulant lifestyle of corporate materialism. Blowing up the condo is a literal comment on–and Jack says as much in his narration–and destruction of the consumerist lifestyle he had been leading.

Tyler’s invitation for Jack to hit him introduces the new world of pain, chaos, and raw experience. The contrast between the perfect IKEA-furnished condo and Tyler’s filthy, grim, decaying Victorian* only highlights this world-shift.

In short, the world has shifted for Jack, and Jack has actively walked into the shift.

*Which TBF is a clear improvement over what you often find in London.

Takeaway: It’s one thing to blow up the character’s life (literally or metaphorically), but this must be paired with a conscious choice that indicates she’s ready for more. Highlight this, when appropriate, with a physical shift in location.

Writing Exercise:

Consider the Paper Street house. Think of a way that your protagonist can physically embody the new reality. Make it vastly different from the world of Act I.

- Sunset Boulevard (1950): The House on Sunset

Scene Cluster:

- Event: Joe agrees to read Norma’s script. He hates it and is looking for an excuse to leave, but by the time he finishes, he’s drunk enough to have concocted a crazy idea…

- Choice: The idea: Joe pitches himself as a script doctor to Norma Desmond (because she has money and he needs money). Norma accepts.

- Location shift: Joe is moved, somewhat against his will, into Norma’s mausoleum of a Hollywood mansion.

Norma’s mansion might well be one of the textbook examples of the physical New World in cinema. You can see the dust and age, the clutter. Max plays creepy organ music and there’s a dead chimpanzee, for fuck’s sake. You can almost smell the despair.

But Joe chooses this world. He is desperate, but he doesn’t have to engage with Norma like this. He’s sleazy enough to become the enabler of her deranged fantasy for a boytoy’s allowance, but along with this comes something he never bargained for: Joe is now a star player in her delusion.

Just as we saw in Fight Club, Norma’s mansion has a personality. It represents the graveyard of Norma’s dreams–and her once-stellar career.

Takeaway: Almost certainly the “new world” of Act II will be a metaphorical reflection of the central theme of the film. In the case of Sunset Boulevard, of course, this means faded glory, delusion, and the price of (Joe) selling out.

Writing Exercise:

Design a setting for Act II that intentionally reflects your story’s major themes.

For example, a story about addiction might place its second act in a crack den (or law office full of Adderall, for that matter).

If the story is all about trust, then the characters might be placed in a situation where secrets are impossible: a scenario that involves mind-reading, or risk of perjury (although keep that one on a short leash; courtroom dramas often suck–look at Joker 2, FFS).

- Die Hard (1988): Building as Battlefield

Scene Cluster:

- Event: Terrorists seize control of Nakatomi Plaza.

- Choice: John McClane decides not to escape but to actively fight back.

- Location shift: McClane transitions from party guest to rogue combatant living within the guts of the building.

John McClane starts simply as a man trying to reconnect with his estranged wife.

When terrorists storm the Christmas party, he has the chance to run, hide, and wait for help. But he doesn’t.

McClane makes the deliberate decision to fight back and do whatever possible to save the hostages. This early choice shifts the entire trajectory from from family drama to survival thriller.

Note that the location doesn’t change outwardly—the entire film is set in Nakatomi Plaza* —but the nature of the location obviously transforms. The building itself becomes enemy territory.

That is, McClane’s relationship to the space changes fundamentally. Once an awkward party guest, now a guerilla fighter inside enemy lines.

Takeaway: It is not strictly necessary to change physical locations in Act II. However, if not doing so, it is vital to change how a character relates to her environment.

This space of course feels entirely different after the protagonist’s life-defining choice.

Writing Exercise:

Consider the location of Act I. Use that location, but track a tonal or structural shift in the narrative

Make this space more intimate, dangerous, or surreal (as the story requires) as you break into Act II.

*Curiously enough the real-life Sony building, in a film financed by Sony.

- The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999): Arrival in Italy

Scene cluster:

- Event: Tom Ripley lands in Italy.

- Choice: Tom makes active effort to insinuate himself into Dickie’s life.

- Location shift: From Manhattan to Italy (Mongibello, Rome, Venice, at different times).

This act break actually takes quite a long time, but then again it’s a long film.

Act I takes its time. It watches Tom as he charms his way into opportunity and lands the job via Mr. Greenleaf. The world truly changes, of course, when he arrives in Italy.

As soon as Tom arrives, he is laying the groundwork for what we initially take to be friendship, but turns out to be something much more sinister.

Tom’s choice isn’t verbalized all at once. It builds. In fact, there’s a good argument to be made that Tom isn’t even consciously aware of it until much later.

(Aside: By my reckoning, this is as a consequence of dealing with the fallout of the murder–but I’m admittedly very polluted by the (much better) novel where we get more insight into Tom’s psychology.)

Tom’s actions—mimicking Dickie, aping his routines, trying on his clothes—hint at the direction of his desire. We can’t tell whether Tom wants to fuck Dickie or to be Dickie. Soon enough, we figure out which.

Takeaway: Act II can begin with a sense of openness or possibility; in short, a fantasy world that the character thinks they can control.

The character gets what they wanted. Then it turns wrong.

Writing Exercise:

Write a short (250-word) internal monologue from your protagonist as she enters her “dream world.”

What does she believe will happen next? How will life pan out spectacularly?

Then write one sentence to hint at how the whole thing falls apart.

- Strangers on a Train (1951): The Murder Happens

Scene Cluster:

- Event: Bruno kills Miriam, Guy’s estranged wife.

- Choice: Guy decides not to go to the police—instead, he chooses to resist Bruno privately.

- Location shift: This one is mental as well as social. At this point, Guy’s world is one where he’s under suspicion–and constant police surveillance.

This transformation is essentially entirely non-physical.

Bruno, a charming psychopath, believes he and Guy agreed to swap murders. Or at least he believes that if he “holds up his end of the bargain” that he can manipulate Guy into committing the murder he’d like to have accomplished.

As soon as Bruno kills Miriam, Guy enters a new psychological reality. At this point, he is implicated in a murder he did not commit.

At this point, he is followed by detectives, hounded by Bruno, and he enters a world with totally different rules from the ones he’s used to.

Guy stays in similar physical locations, but his mental landscape is irrevocably altered. At this point, he essentially lives within Bruno’s delusion. The choice to resist this fantasy (rather than to confess–and potentially be implicated–or go along with it and become a murderer) defines his trajectory.

Takeaway: The Act II break can be a shift in worldview.

A character doesn’t necessarily change physical locations, but realities.

If someone commits a crime on your behalf–and you become the prime suspect–the world certainly doesn’t look the same as it once did.

Writing Exercise:

Consider a situation where your protagonist learns that someone has acted in their name without permission.

Depending on the act, how does this change how your character exists in their world? What sort of decisions does it force?

The Break Into Two as Rupture

Act II breaks will almost certainly be a rupture, a reorientation, and most importantly, a choice. Whether that choice is to punch some guy because he asks you to, move in with an unstable stranger because you smell a job opportunity, start a lone fight against 12 well-armed terrorists, or lie to the police—it signals the beginning of something irreversible.

When possible–or reasonable–it’s recommended to externalize that shift with a new space.

In more advanced situations, this can be done psychologically, but in any case, the “new world” must feel foreign, wildly destabilizing, and governed by entirely new rules.

What These Five Examples Teach Us

| Film | Event | Choice | Location Shift |

| Fight Club | Condo explodes | “Hit me” / Moves in | Consumerist apartment → Decrepit, squatted chaos house |

| Sunset Boulevard | Fleeing repo men | Accepts Norma’s offer | Hollywood → Mausoleum of fading dreams |

| Die Hard | Terrorist takeover | Chooses to fight | Office tower → War zone |

| Talented Mr. Ripley | Arrives in Italy | Begins imitating Dickie | America → Tyrrhenian fantasy world |

| Strangers on a Train | Bruno kills Miriam | Guy stays silent | Normal life → Delusional nightmare (and being a suspected murderer) |