Seinfeld for Screenwriters: 3 Exercises to Build Your Irony Muscle

“A show about nothing.”

The show’s elevator pitch echoes decades later.

Yet Seinfeld is about something: it is about irony. Every episode of Seinfeld is an irony engine firing on all cylinders.

What separates Seinfeld from most crap sitcoms is that the show was never limited to a single ironic premise (which is basically the point of a sitcom). Rather, Seinfeld’s superpower lay in its modular structure that would allow for a different ironic concept each week.

Here we examine Seinfeld’s Irony Machine.

I. The Death of the Core Concept

In traditional sitcoms, the concept is the be-all end-all:

- The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air: a street-smart teen from a poor background moves in with his wealthy relatives.

- Home Improvement: a guy who knows everything about tools is clueless about his own family.

- Full House: a widowed dad brings up three daughters with the help of his male cousins (or something like that… been a while).

Sure, yeah, this works well at the beginning. Eventually, the concept dulls. We’re used to the situation.

Essentially, most sitcoms ring the bell of their inherent irony over and over. The central tension is so unbelievably tired that characters do more and more ludicrous things to get our attention. Someone jumps over a shark on waterskis. Et cetera.

Seinfeld, however, was so anti-conceptual that it could never wear out. Its real genius lay not in creating a durable ironic premise, but rather it was able to exploit short-term ironic situations.

Every episode was a new show. It was a different mini-sitcom that just happened to work with the same flexible cast of archetypal characters.

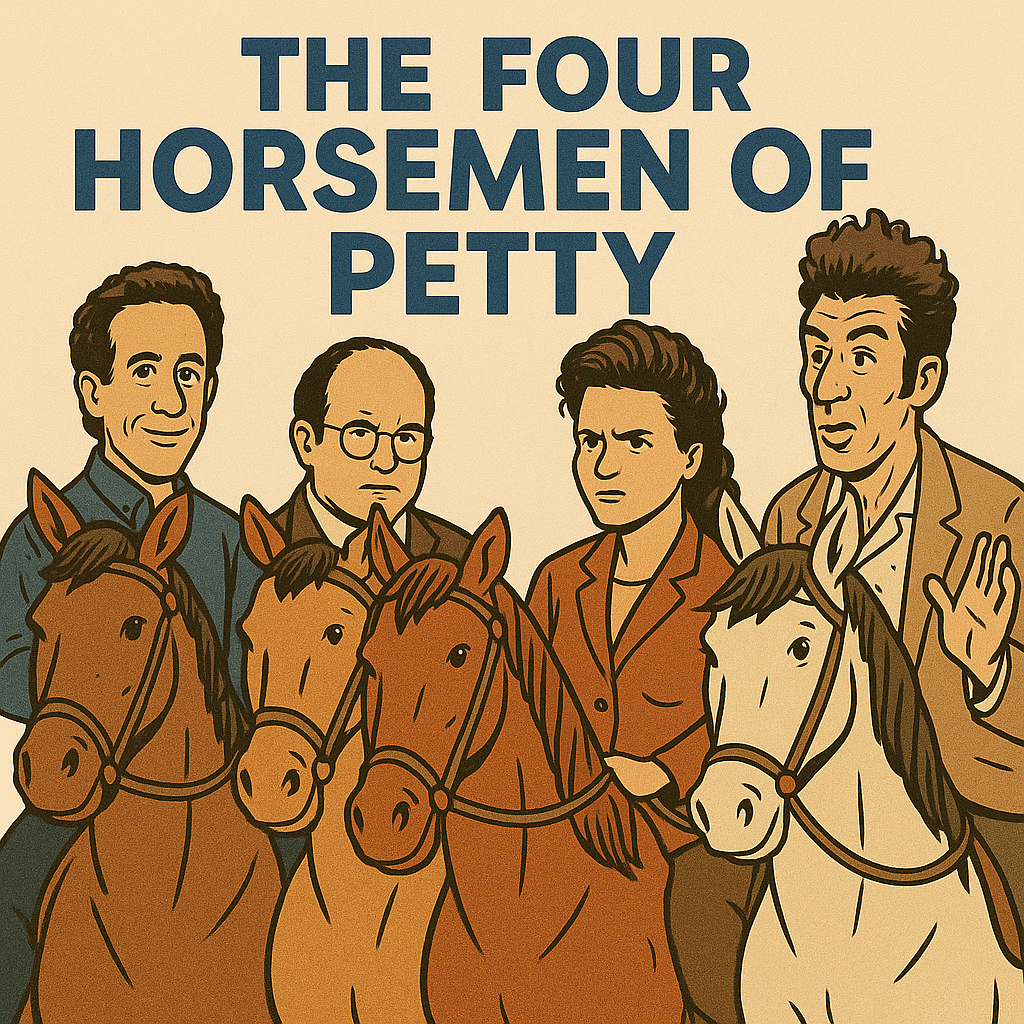

II. The Four Horsemen of Pettiness

Jerry, George, Elaine, and Kramer are each archetypes of a specific flaw:

- Jerry: the smug observer, who can’t emotionally invest in anything

- George: the neurotic loser, forever trying to cheat the system (and never succeeding)

- Elaine: the prideful individualist whose assertiveness backfires

- Kramer: the chaos agent who exists in a parallel dimension of logic

As the immortal dictum from the Seinfeld writers’ room goes: “no hugging, no learning.”

These characters were designed to collide and play off each others’ weaknesses. They never learn their lesson, so they’re always fresh for the next ironic adventure.

Any sufficiently ironic situation could deliver comedy gold. The individual episodes had arcs, but the show as a whole barely did (yes, there were a few throughlines, but bear with me here…). This is how Larry David and his team of writers could build an entire narrative around violating a petty social rule–regifting, double-dipping, close talking, etc.–and we still talk about it over 30 years later.

III. Seinfeld’s Weekly Concept Showcase

What is irony?

In the world of narrative design, irony happens when:

- Expectations are reversed

- Hypocrisy is exposed

- Flaws are punished (or, occasionally, rewarded in absurd ways)

- Characters act against their own interests

- Justice arrives—but sideways, not cleanly

Now apply that definition to nearly every episode of Seinfeld and you’ll see what’s going on.

A few iconic examples:

- “The Contest” – A challenge for who can go the longest without (ahem) self-pleasure. Social taboos collide with self-restraint.

- “The Marine Biologist” – George lies to impress a woman. That lie leads to an absurdly specific test of his fake identity. If he is to win, he risks total humiliation.

- “The Opposite” – George decides to do the opposite of all his instincts. For once, life rewards him. Until it doesn’t.

- “The Puffy Shirt” – Jerry agrees to wear a ruffled white pirate shirt on a national TV appearance because he doesn’t want to argue with Kramer’s “low-talking” girlfriend” and torches his career in the process.

- “The Soup Nazi” – The owner of a soup shop is allowed to behave like a rigid authoritarian to his customers because of the quality of his soup. However, once Elaine serendipitously gets hold of his recipes, the magic is lost.

Any of these stories could easily have worked as the concept for at least a full season of most mere sitcoms. On Seinfeld, however, they’re just this week’s irony. Next week is on to something totally different.

IV. How Larry David Built the Irony Engine

Larry David is the Irony Machine.

Larry doesn’t merely create characters and situations. Larry mines contradictions. Larry identifies hypocrisies. Larry has an unnatural gift for pinpointing exactly where social rules fail—and then builds an entire scenario around that tiny crack.

Larry assumes that everyone is selfish, that everyone lies, and that everyone has an agenda. Larry is waiting for the mask to slip.

Popular it may not be, but it is surprisingly accurate. Stories built around this premise are cringey, relatable, consistent, and inventive in how they mine everyday issues for hilarity.

As we can see, Curb Your Enthusiasm is essentially Seinfeld with the gloves off. It strips away the laugh track and the network censors to give raw, unfiltered irony.

V. Seinfeld vs. the Sitcom Status Quo

Contrast the Seinfeld approach to a more conventional sitcom.

Take Mad About You—the show that originally aired immediately before Seinfeld during several of its seasons. It was about a neurotic but loving married couple navigating life together in New York.

Honestly, you can only watch the same couple fight about toothpaste, an anniversary dinner, or whatever so many times.

Seinfeld intentionally threw out love arcs, job consistency, and moral lessons.

On purpose.

Seinfeld unburdened itself from tired sitcom moralizing, replacing this with a focus on the absurdity of human existence. The characters in any situation, whether lost in a parking garage, waiting in line at a Chinese restaurant, or at a rental car desk, would be able to generate more than enough irony to power a 22-minute episode.

VI. Seinfeld for Screenwriters

Exercise: Build Your Own Seinfeld Machine

Try the following exercises to write comedy, build story ideas, or simply sharpen your social observation.

Exercise 1: Micro-Irony Generator

Take any minor social rule. Something polite. Something unspoken. Bonus points if it’s stupid. Now imagine what happens when:

- Someone takes it too far

- Someone completely ignores it

- Someone manipulates it for personal gain

Example: Holding the door open

- What if someone always holds the door open—even if you’re 30 feet away? (awkward)

- What if someone lets it slam even though you’re right behind them? (asshole–or did they simply not see you?)

- What if someone pretends to not see you to avoid the social contract? (let’s face it, they’re probably just English)

Turn this into a full scene.

Exercise 2: The George Test

Consider a tiny lie someone might tell to gain an advantage (better if there’s a reason for it). Now expand the consequences of that lie to a ridiculous level, and force the character to live inside those consequences.

Example: “I’m fluent in French.”

Imagine this gets the person roped into a fancy dinner among her interlocutors’ French extended family. Write the scene where everything falls apart.

For extra credit, go Full George: write the case where she actually pulls it off, but in the most humiliating way possible.

Exercise 3: Kramer Logic

Invent a character who behaves by a totally different set of rules from everyone else—crucially, he believes 100% in these rules.

The charm isn’t merely in Kramer’s odd behavior. It’s how he owns it.

Prompt: Pick something ludicrous that your character believes. Eggs taste better when cooked in the dishwasher. Shampoo is a scam. He will improve his eyesight from only eating carrots for a month. Have him rope another person into the problem, unwillingly. Write the confrontation.

Exercise 4: Irony in Reverse

Pick a ridiculous outcome. Build a logical (but ironic) path to that ending.

Ending: Your character gets banned from the local bakery for “loitering.”

Now justify that ending in five steps, with step five being the ending. What original (mostly) innocent intent brought use to this point? What went wrong along the way?

VII. Seinfeld’s Legacy

Seinfeld gave us a format where consequences were inevitable, but never moral. Justice existed, though filtered through absurdity and ego.

The sitcom field is still littered with moral lessons and redemptive arcs. Hell, they probably still have “Very Special Episodes.”

Seinfeld still stands out as a monument to pure conceptual brilliance. People being terrible in petty, ironic ways.

No hugging, no lessons.

What We Learned from Seinfeld’s Irony

Seinfeld teaches us that story need not be about growth or victory. It can be about collision.

Where would Peep Show or even Succession–and obviously many other shows–be without it?

Seinfeld showed people actively putting themselves in situations that prey on their flaws. About the absurd things that people do, say, and believe. The way petty or arbitrary systems unravel.

Seinfeld gave us a hundred miniature sitcoms.

What happens when this tiny crack in the social order gets blown wide open?