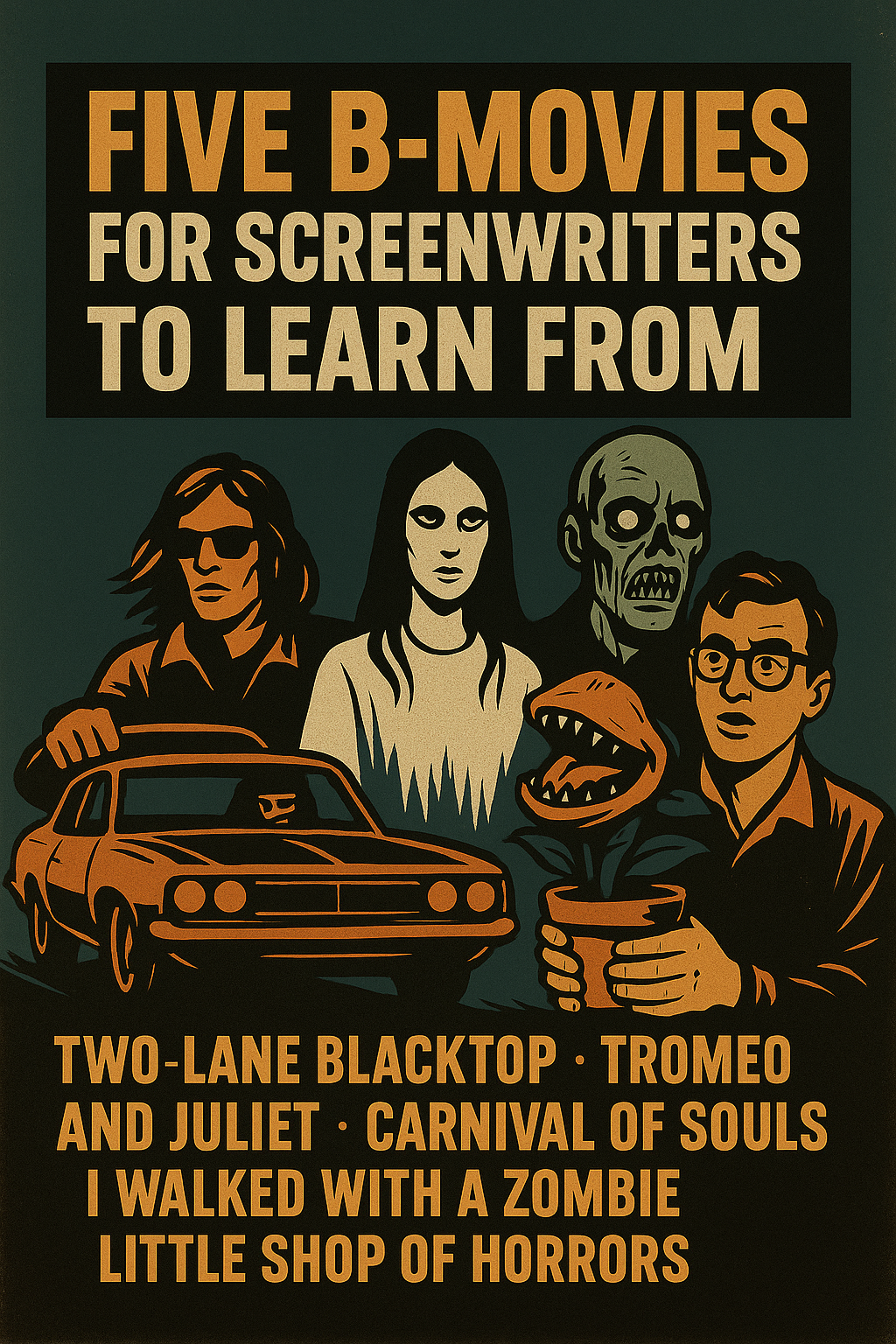

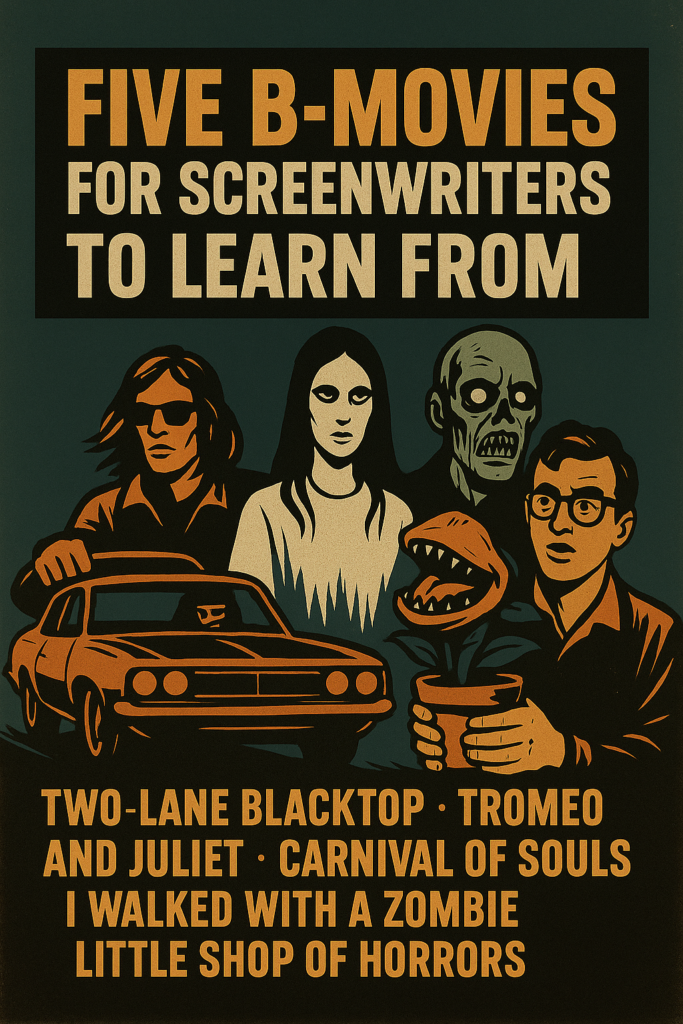

Five B-Movies for Screenwriters to Learn From

Budget limitations, genre constraints, and creative freedom: here’s how low-budget cult classics made the most of limited resources.

Screenwriters often think they need a big budget to tell a big story.

But the truth is, great writing thrives under constraints. Whether it’s time, money, or production value, B-movies have long served as fertile ground for innovation in screenwriting if only to accommodate these facts.

The five films below weren’t blockbusters—but each offers a masterclass in tone, structure, irony, or adaptation.

Most of all, they prove that if your script is strong enough, the rest will follow.

1. Two-Lane Blacktop (1971)

Directed by Monte Hellman | Written by Will Corry & Rudolph Wurlitzer

At face value, Two-Lane Blacktop is a road movie about drag racers. But in truth, it’s a meditation on the emptiness of motion and the quiet absurdity of American masculinity.

The characters are barely named (they’re credited as “The Driver” and “The Mechanic”). Notably they are played by the musicians James Taylor (yes, the one your dad listens to) and Dennis Wilson (yes, the one who walked into the ocean and never came back). The monster character actor Warren Oates is unforgettable as the antagonist called “GTO” and the soon-to-be-tragic Laurie Bird provides a haunting turn as “the Girl.”

The story offers no tidy resolution, or for that matter, a clearly-defined climax. Yet this existential minimalism invites deep emotional and philosophical engagement.

What makes this script so valuable to screenwriters is how it sustains tone and mood with very little dialogue. The story drifts, yet never feels like it’s lost. The emotional terrain echoes the emptiness and loneliness of existentialist literature (think Camus or Beckett) with the backdrop of a long-lost Route 66.

The film is looser and more poetic/meditative than the films it is frequently compared to, such as Vanishing Point.

Takeaway: Your plot doesn’t need to be tightly wound to feel meaningful. If you can evoke a consistent mood and shape character arcs subtly, your audience will follow. And Warren Oates.

Writing Exercise:

Write a 5-page scene where two characters say almost nothing, but their emotions and intentions are clear through environment, action, and silence.

Set it on a long road trip. Do not name the characters.

Your goal: make the audience feel the relationship and its nuances without overt exposition.

2. Tromeo and Juliet (1996)

Directed by Lloyd Kaufman | Co-Written by James Gunn

Tromeo and Juliet is more than a sleazy riff on Shakespeare. It definitely is that, but so much more.

While the dialogue veers from Shakespearean verse to modern profanity, and the tone careens between horror, sex comedy, and tragic romance, the emotional spine of Shakespeare’s original story holds.

James Gunn–yes, that James Gunn–co-wrote this exercise in genre confusion, absurd violence, emotional mischief, and general irreverence. Along with a tidy dose of sexual anarchy and bodily fluids.

The story remains Shakespeare’s, but the aesthetic becomes total chaos–but Kaufman and Gunn pull it off beautifully. This is a good demonstration that structure can often outweigh style. A solid story such as this can support outrageous, absurdist reinterpretation.

Takeaway: You can be sex-obsessed, anarchic, and intentionally shocking—if you’re careful to honor the core structure and emotional truth of the original.

Writing Exercise:

Pick a widely known classic: a Greek myth, fairy tale, or even another Shakespeare play.

Write the logline (or even a beat sheet) for a modern genre-based adaptation.

Preserve the core themes, but alter tone, time, and place completely. Go as extreme as possible without losing sight of the core emotional structure.

3. Carnival of Souls (1962)

Directed by Herk Harvey | Written by John Clifford

The influence of this film far outweighs its budget. Loosely based on Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”, Carnival of Souls is a horror film with arthouse sensibilities.

Harvey cited the influence of Bergman and Cocteau in making the film. Some of the visuals also recall German Expressionism. In any case, its dreamlike pacing, eerie atmosphere, stunning black-and-white visuals make it punch above its weight.

The brilliance of the script lies in the central irony: Mary is the sole survivor of a car crash, only to find that she is unable to meaningfully engage with the world after this experience. This metaphor allows for the skilled use of vast Utah landscapes and the gigantic, haunting carnival set.

Further to that, she is consistently haunted by white-faced ghouls who will ultimately catch up with her.

It’s a low-budget film, so there are moments where things go a bit funny. Notably, sometimes the acting falters. To Harvey’s credit, however, the mood is consistent, and the metaphor of death pursuing Mary despite her narrow escape* never wavers.

Takeaway: Atmosphere can carry a film when dialogue and acting are shaky. If your theme is clear and ironic, and your visual world supports it, your story will resonate.

*Think Final Destination, but used as an example in film school.

Writing Exercise:

Write a 1-page silent scene where your protagonist wanders a liminal space (e.g., an abandoned building, an abandoned small town, a nearly-empty airport.

Write for visuals–not camera or lighting direction–but try to force the hand of the director and DP. Think visually. Describe in a way that can only be shot a particular way.

The goal is to suggest something is “off.”

Afterward, write a few sentences explaining what this scene symbolizes about the character’s state of mind. Does it achieve this. Give it to someone else. Do they think it achieves this? Revise until the reader believes so.

4. I Walked With a Zombie (1943)

Directed by Jacques Tourneur | Produced by Val Lewton

Imagine Jane Eyre set in the Caribbean—with voodoo. Basically a Troma film, from the sounds of it.

Not precisely, but that is more or less the pitch for I Walked With a Zombie. Produced by horror legend Val Lewton, the film wraps a Gothic melodrama in late colonial-era supernatural trappings.

The layering of these apparently disparate genres yields a surprisingly potent emotional effect.

The plot follows a nurse caring for a comatose woman on a plantation. This woman has lately been the reason for a feud between two plantation-owning brothers*. The “zombie” element is subtle and haunting, used as metaphor more than spectacle. The woman in question makes for a particularly attractive zombie.

Ghastly makeup and jump scares are nowhere to be found. The story’s core strength lies in its slow, steady moral unease. The film raises strong questions about agency, death, and colonial guilt.

Takeaway: Genre films can carry serious thematic weight, especially when built on familiar plots. Instead of reinventing everything, consider infusing familiar stories with new moral and cultural stakes.

*The story is contemporary to the film’s release–1940s–but sugar plantations existed even if technical slavery didn’t.

Writing Exercise:

Take a well-known Gothic or melodramatic setup (e.g., a governess, a secret marriage, a haunted house) and transplant it into a different cultural setting. Particularly if this involves something largely confined to a different genre, like a supernatural or science fiction element.

Sketch a 1-paragraph outline. Consider the beliefs, superstitions, or political tensions that could reframe the emotional mistakes or allow for potent in-story commentary.

5. Little Shop of Horrors (1960)

Directed by Roger Corman | Written by Charles B. Griffith

Shot in two days with recycled sets, Little Shop of Horrors is a marvel of economical filmmaking. It combines farce, horror, tragedy, and satire in a black comedy that’s still fresh more than 60 years later.

The plot is simple but potent: a nerdy florist discovers that his new tropical plant, named after the girl he has a crush on, has a taste for human flesh. What’s more, feeding the plant gives him a taste for killing.

The story escalates naturally, with each bad decision logically following the last. Corman and Griffith use the absurdity of the premise to explore deeper questions about ambition, guilt, fame, and the lengths that men will go to in order to impress women.

The result is tight, self-contained, and shockingly clever. Plus Jack’s cameo.

Takeaway: If you’re short on time and money, lean into simple stories with high-concept irony. Assume a restriction of: three rooms, one location, few characters, and a clear cause-and-effect story. For everything else, go nuts.

Writing Exercise:

Develop a contained, ironic horror premise that could be shot in 48 hours using one main location (bonus points if indoors).

Write a short synopsis (1-2 paragraphs) that outlines the hook, irony, and how each decision raises the stakes.

Screenwriting Laboratories

The best B-movies are more than cult curios or “so bad they’re good” spoon-throwing extravaganzas.

These films are where risks can be taken–largely because no one is watching. Free from the prejudices and constraints of studio polish, the greatest among these films can demonstrate what really matters: character, irony, structure, theme, and tone.

If money is non-existent and you’re definitely not hiring name actors, the writing is the place to shine. Note how few of these films star people we’ve heard of today (at least as actors!). When the writing works, the film works. Make your film stylish, strange, or more within the limitations you have. Let constraints make the art and you may just have a classic on your hands.