Why Does Concept Matter So Much?

Simple: no one cares about how brilliant you think your idea is. They literally [1] only care about how much money it’s likely to make for them.

Yeah, sorry. Someone probably forgot to tell you that in film school.

That’s most likely because the film school was more interested in making money from you than actually getting you a foothold in the film industry.

What matters is the quality (read: saleability) of your idea.

And maybe you really do have a genius idea. Maybe it’s the next Jaws or Iron Man or Funny Games. Yeah, I just slipped that one in. Close the laptop and go watch it.

HOWEVER, if you can’t communicate that idea’s brilliance effectively, you’ll get absolutely fucking nowhere with it.

Good Concept Doesn’t Mean “High Concept.”

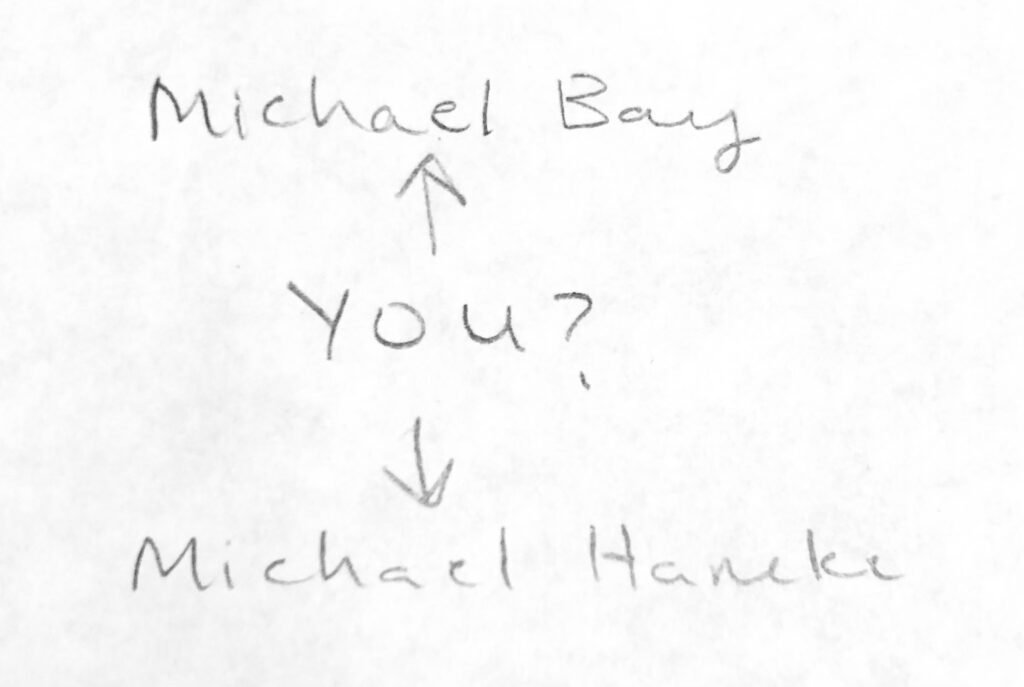

There are undoubtedly a lot of naysayers out there who are worried that I’m talking about some Michael Bay-style PG-13 explosion-ganza when I talk about “concept.”

Hardly.

Michael Bay et al. create what’s commonly referred to as “High Concept” films.

High Concept doesn’t necessarily mean that a movie is bad, but it does lend a film to being Over the Top (henceforth “OTT”) in execution. As Michael Bay well knows, this can detract unforgivably from the power of the story itself.

With that in mind, what this book discusses is a much more general definition of “concept.” To wit: every film has a “concept,” but not all films are High Concept.

As Above, So Below

“Low Concept” films also exist.

These are films that are very hard to describe and very hard to sell. The difference between High and Low concept is that High Concept is easy to sell because the concept alone makes people interested; the execution is an afterthought. Ask Roger Corman.

Interestingly, Low Concept films tend to be made by established directors. That’s quite simply because they’re sold on the name and reputation of the director or lead actors. These are the types of films that very often win Oscars.

The reasoning for this, put simply: old people love boring stories told well. Oscar voters are predominantly film industry veterans (read: old people). Ergo, such films tend to win Oscars.

OK, that might not be in every single case.

In nearly 90 years of Oscars, there have been a few exceptions where a thriller or a musical—which by their nature need to be somewhat High Concept–won. Read: The Silence of the Lambs, The French Connection, West Side Story.

Nevertheless, it’s fairly unusual for a High Concept film to win an Oscar.

Hybrid Concept

The thinking screenwriter’s anathema, or: you’ll have to do this to speak to creatures on an evolutionary level somewhat below you.

More than anything, this is a method of concept creation rather than an actual description of the concept of a film.

Few serious writers really think this way, however. Check out Robert Altman’s The Player for a brilliant send-up of this type of thinking.

The principle of Hybrid Concept is pretty straightforward: simply take two famous films and slam them together with the word “meets.”

For example, “Dumbo meets Showgirls.”

You know, an ex-crack-whore baby elephant runs away to join the circus and soon finds that he’ll have to adopt the unpleasant traits of his own worst enemy before he can learn to fly and save the circus from bankruptcy. That old chestnut.

Maybe there’s a better way to do it. If so, I’d be glad to hear.

The Right Kind of Concept

Let’s call it “Good Concept” for lack of a better term. Good Concept will be our major focus in this book. These are the types of films that stick with you–without even trying to remember them.

Put another way…

They’re not High Concept—risking a letdown or buyer’s remorse when the execution doesn’t live up to the premise.

They’re not Low Concept—boring on paper even if watchable on screen.

Rather, they are films where the story seems compelling, natural, and correct. It has a hook but it doesn’t feel cheap. Hell, who knows… you might even be able to squeeze them into some sort of Hybrid description, but that will likely be a stretch.

If you’re still fixated on the Hybrid thing, a Good Concept film is the film that you would use as one of the two blended parts of a Hybrid Concept.

One of the most important principles of Good Concept is that we balance the irony correctly so that the audience won’t experience Buyer’s Remorse as with High Concept.

Think of it like a chili dog. It looks and smells incredibly tempting, but about two minutes after you jam it down your gaping maw, you begin to think, “Gee, maybe that was a better idea in principle than in practice.”

The inverse is true of Low Concept. Take a film such as Michael Haneke’s Amour, then try to sell it to a young, vital person.

Without selling the fact that it is Michael Haneke and Michael Haneke is one of the great filmmakers of our time, that is [2]. Seriously, who wants to spend two and a half hours watching a movie about the knock-on effects of an octogenarian’s stroke?

Let’s be honest here: it could be the greatest movie since sliced bread, but it still sounds depressing as shit.

It follows that for Good Concept, we want to give the audience a reason to want to know more about what happens, yet also to make the execution approachable or “saleable” to a civilian.

[1] To clarify, this is the dictionary definition of “literally,” not the spastic-twelve-year-old’s-tic definition that has taken off in the past few years even amongst those with triple-digit IQs (thanks, Rob Lowe): that is, not figuratively, not actually, not “sort of.” As in “that is the one thing that matters.” If such people say something other than The Cheddah matters, they are deluding themselves as much as they are stringing you along. Sorry to break it to you.

[2] “A feature film is twenty-four lies per second.” —Michael Haneke. Boom.